Why Do Americans Feel Entitled to a Leadership Role on Climate?

I'll say it: in any global convening, the ones jockeying for power or money or attention or their way are the Americans (Wait, aren't you American, Amy? I am!). It's as true on climate as it is in any other realm, but for my money it makes the least amount of sense on climate. The U.S. didn't just lead the world on emissions for decades, it also created and spread most of the tactics used to block climate action. It has always had the largest number of people believing in and amplifying climate denial. It was American companies that orchestrated the global industry's response on climate, and it was the U.S. that blocked Kyoto. All of that means Americans hold enormous responsibility for climate obstruction, which means we should definitely be putting the most money and effort into removing the obstacles to climate action, but that's not the same as being entitled to lead that effort.

And that misunderstanding is, itself, so very American. If we're going to be heavily involved, obviously we're going to lead, lol. Which brings me to the primary reason I think us Americans are uniquely unsuited to be the ones to lead the world out of climate catastrophe. While our country is, as all the headlines rightly proclaim, deeply divided on all sorts of moral, political, cultural and ethical issues, there is one unifying thread underneath it all, a terrible sickness that's been eating away at the county and its citizens throughout its existence: hyperindividualism. Individualism and competitiveness have driven the U.S. and Americans to some great accomplishments, to be sure, but hyperindividualism is something else entirely, it drives a win-at-all-costs competitiveness in American society that's hard to shake off and that is entirely at odds with the sort of collaboration required to stop a global crisis. I see it cropping up in ways small and large in climate spaces all the time, from the way U.S. negotiators drive international climate discussions to focus on coal, rather than oil and gas, to the way American advocates tend to talk over and erase the work of their counterparts from elsewhere in the world—particularly the Global South, but it happens to Europeans, Aussies, Kiwis and Canadians too, we are equal-opportunity egotists. A key difference, at least in my experience, is that folks from the Global South tend to see this immediately for what it is, while Global Northerners are sometimes impressed or blinded by our bravado at first; all that confidence must be rooted in something, right?

It helps to understand where this hyperindividualism came from to understand why it makes us a bad choice to lead a global movement against self-interest (because what is the climate crisis at its core but the triumph of self interest over the common good?). For a start, the U.S. was the first new country formed after the Enlightenment, so it's basically impossible to separate American identity from the ideals of the Enlightenment, some of which were great—you don't need to be religious or noble to know things, society owes all of us basic rights, there's a scientific way to understand how the universe works; some not so great—the advent of race as a classification structure, followed quickly by racism. Then there's the fact that the vast majority of people who left the Old World for the New and decided to fight the people they found there for land were Calvinists, a particular type of Protestant reformers who believed that only God could lead the church (no priests, so none of the hierarchy of the Catholic church) and that every person could understand the Bible in their own way and build their own direct relationship with God. Men were the heads of the family, but also the ones responsible for the souls of their family and thus the religious upbringing of any children. So you've got people who are willing to leave everything they've ever known for a chance at a better life, who also feel that life is owed to them, who believe they each have a direct relationship with God and who have rejected the idea of "experts" interpreting things for them.

And layered on top of that you have Enlightenment ideas, one of which was the notion of a social contract. Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Thomas Paine thought and wrote a lot about social contract theory. They all had different ideas, but it boils down roughly to the idea that individuals have to give up certain rights as a trade-off to the security and stability provided by living in a society. With the Enlightenment throwing off the idea of either aristocracy or church leadership running things, this notion of the social contract became incredibly important: what does the government owe the people, and vice versa? Where do individual rights and the common good meet, and how should the lines between the two be drawn?

The U.S. opted early for more individual rights, while also not treating the vast majority of humans as individuals in the eyes of the law. Only land-owning white men were allowed to vote for the first 52 years of the country's existence. In order to justify slavery and indigenous genocide while building the first country ever founded on the basis of equal rights, the founding fathers had to do some real mental gymnastics, which twisted America's version of the social contract before the country even officially existed. Subsequent generations further stretched and warped the meaning of "natural rights" pushing the American social contract further and further toward an agreement that protects a select few, yet obligates all, that places the individual above the public good in every meaningful way.

Also worth noting: by the time all citizens were granted the vote, the country had already begun to treat corporations as individuals. The Supreme Court first began to suggest the idea of corporate personhood in 1886 and by 1897 referred to it as "well settled law" that "“corporations are persons within the provisions of the fourteenth amendment." So more than 20 years before women got the right to vote, the U.S. had conferred legal personhood on corporations.

As currently interpreted and applied, the social contract in America requires that individuals take personal responsibility for both the impacts of systemic problems, and for developing solutions to them. You’re poor? You aren't working hard enough, or perhaps you just lack talent and brains. You’re discriminated against? You should have been more polite, dressed better, worked harder. Worried about climate change? Better have zero personal carbon footprint or you can't talk about it at all. Struggling to balance work and parenthood? Maybe you shouldn’t have had kids, or a career (depending on your race and gender). Can’t afford healthcare? Should’ve gotten the right job. Can’t afford to retire? Shoulda saved!

Those of us raised in that context inherit the idea that we can rely on no one but ourselves and that we're all in competition for finite resources. And while there are many cultures within the U.S. that don't ascribe to this idea, particularly the Indigenous nations that occupied this land before colonization, because it underpins the systems we all live under, no one escapes entirely unscathed. The result is people who either find it very hard to trust strangers, because they've been burned trying to collaborate with people who want to compete, or who have bought into the hyperindividualism and take an ends-justify-the-means attitude toward winning. When that shows up in the climate space, it tends to have a layer of moral superiority to it as well. I think it contributes not only to a lot of the in-fighting and jockeying for position in climate spaces, but also to the tendency to separate climate from other social issues—something that's far more common in the U.S. than most other places on the planet.

All of which has me wondering recently...in the climate movement, are Americans basically Exxon, demanding our seat at the table only to constantly flip it over and storm out when we don't get our way? It seems like we should at least be making a concerted effort to make sure we're not doing that, to make sure that we're capable of being part of a movement even if we're not leading it. Perhaps the most meaningful way for us to address our role in creating and perpetuating this crisis would be to learn, for once, to listen. To follow and support and amplify rather than take over, to be part of the choir rather than demand a solo, to pay our dues and then shut up for a minute.

Come see Drilled live at The Hollywood Climate Summit!

Grab a spot at the 2024 Hollywood Climate Summit, where we're empowering creators to make a difference through their work. We'll be doing a presentation and panel on the 26th about the "Mad Men of Big Oil," but there's a ton of great programming at the summit and we plan to check it all out. Together, let's write the script for a greener, more sustainable future. As a partner, we're able to offer Drilled readers and listeners a special discount. Use the buttons below to grab a one-day or full conference pass today!

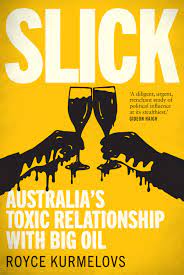

Book Recommendation— SLICK: Australia’s toxic relationship with Big Oil

We brought on a new investigative reporter in Australia last month, Royce Kurmelovs, and he has a new book coming out in August that takes a comprehensive look at the origins of the Australian petroleum industry, investigating what these companies knew about climate change and how they learned to wield influence and insert themselves into all facets of public life. It's a super important read at a time when the world seems to be just waking up to the fact that Australia is both one of the top contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and one of the world's biggest obstacles to climate action.

This Week's Climate Must-Reads

- How 3M Executives Convinced a Scientist the Forever Chemicals She Found in Human Blood Were Safe - The GOAT, Sharon Lerner co-published this epic story with The New Yorker and ProPublica, profiling a scientist at 3M who tried to blow the whistle on forever chemicals, was told to leave it alone and did, and is now coming to grips with what that means.

- Is Big Oil Putting Microplastic in Your Testicles? Sometimes stories are both hilarious and serious and this is one of those times, an absolute banger from Kate Aronoff at The New Republic.

- Inside the Rockefeller Clan’s Intensifying Feud With Exxon A fascinating long read on the ongoing battle between the family that started Standard Oil and one of its most successful progeny.

- How a Climate Backlash Influenced Campaigning in Europe Somini Sengupta digs into how European leaders are dealing with climate being dragged into the culture war.

- ICYMI: LSU's Fossil Fuel Partnerships - This investigation from Sara Sneath for The Lens reveals how fossil fuel companies funding research at Louisiana State University influence research and coursework.