Forget the "Joe Rogan of the Left," Where's the Rupert Murdoch?

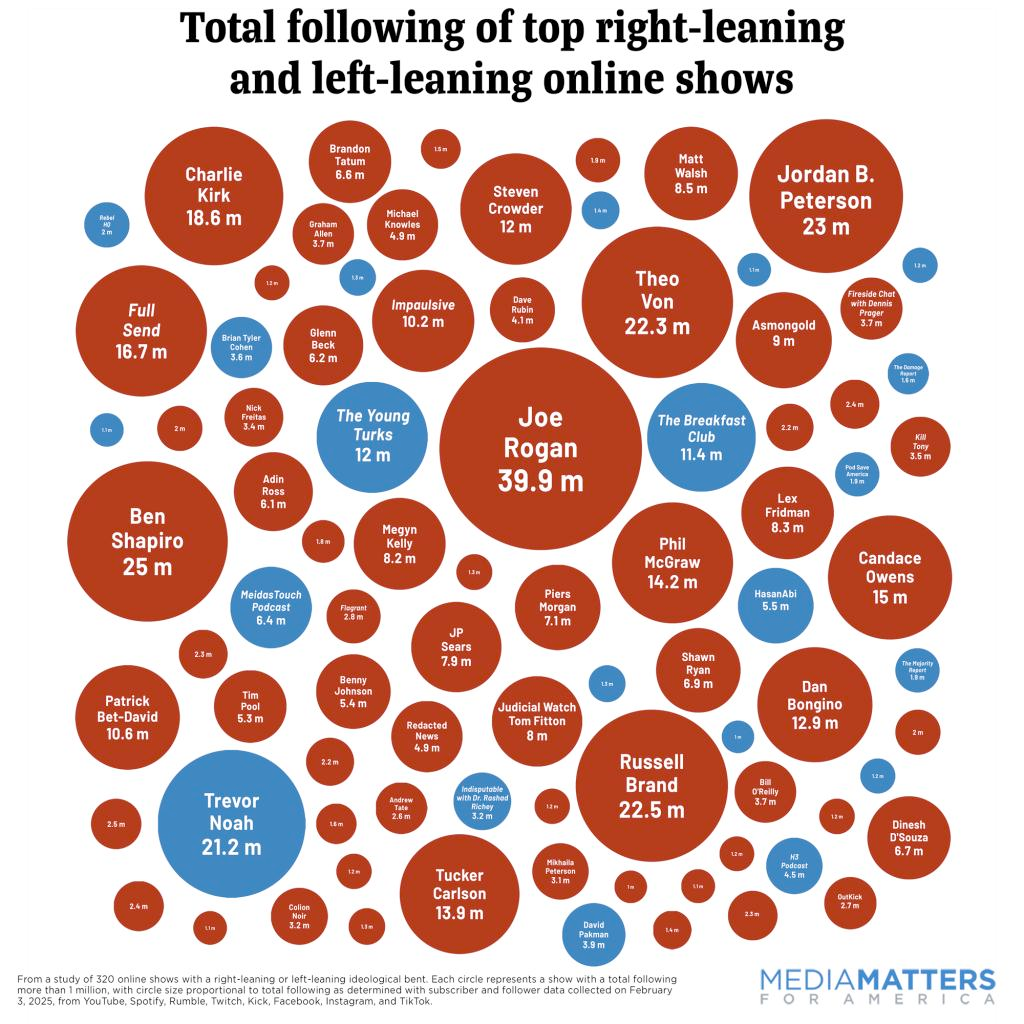

Something can be repeated over and over, a story told ten different ways, and then one particular frame or graphic or turn of phrase makes it take hold. There are plenty of people who claim to know exactly what that special sauce is. I am not one of them. Mostly I figure people just need to hear something at least 10 times before it sinks in. I'm only talking about this phenomenon because it happened in the media-climate-philanthropy world recently when Media Matters put out an analysis of the online media ecosystem that included the graphic below, showing very clearly exactly how much more attention right-wing media is capturing these days than any other sort.

For a brief moment, I hoped it might actually help philanthropists on the left to see what they're up against and act accordingly, but then (through no fault of Media Matters!) the response turned into yet another round of the "we need a Joe Rogan for the left" discourse. Folks, the problem is not that there are no popular commentators on the left, nor is it that leftist commentators lack the "skill" to weave propaganda into a three-hour stoned bro fest. Neither is it a framing and accessibility issue, as it's often portrayed in the many "if only we could make [pick your issue and favorite set of corresponding facts] more funny, accessible, relatable" conversations. All of these responses take a glaring systemic issue and pretend it is an individual one.

For the millionth time, I wish those who worry about media, comment on it, think about funding it, are starting to (finally) understand its importance to democracy would...ASK PEOPLE WHO WORK IN MEDIA about this stuff? And no, your comms guy doesn't count, even if (especially if) he spent a year as a reporter way back when. For those of us who have worked in media for any period of time, and especially those of us who are old enough to have worked in media during the shift to digital, this chart holds some very clear truths that I just have not see pundits or philanthropists or comms experts or campaigners talking about:

Legacy media has lost an enormous amount of influence.

Listen, I can criticize legacy media with the best of them, but I can also see how the shift to independent creators has both created opportunities for journalists and commentators to be more directly responsible to the public and how that shift has eroded many of the norms that once helped to ensure information integrity in some very concerning ways. With the business model for legacy media up-ended by digital, not only have legacy outlets put money once reserved for things like fact-checking into social media and online video budgets instead, but also independent creators have started publications that never included editing or fact-checking systems in the first place. As an independent creator, it is shocking to me the number of both independent and legacy media outlets I come across that no longer do fact-checking or, if they do, have some form of "self-fact-checking" that will never be able to compare to the real thing. The reality is that fact-checking is expensive and time-consuming and most outlets would rather pay for various other things. In the current moment, I can't think of anything more worth paying for, and yet while many foundations would agree, where is the funding for such things?

The question here, then, is not: who is the Joe Rogan of the left? But rather, how do we fund independent creators so that they can implement some of the good approaches of legacy media while also tapping into the benefits of independence? Or to make it pithier, who is the Rupert Murdoch of the left?

While the likes of George Soros and Pierre Omidyar have stumped up cash for short-term investments, nothing remotely close to the rightwing media funding ecosystem exists on the left (ironic, given the endless "liberal media" accusations). In addition to Murdoch, there's the Koch universe of foundations (major funders to right-wing outlets like The Daily Caller), Dick Uihlein (the conservative funder behind Metric Media, an ecosystem of more than 1200 "pink slime" newspapers that purport to be local news but are pay-for-play operations whose clients are corporations and conservative politicians), the Mercers (longtime backers of Steve Bannon and Breitbart News), the Wilks brothers (fracking billionaires who have funded Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Prager U) the Sinclair family (which owns and operates conservative media company Sinclair Inc., which controls about 40 percent of local news broadcasts), and that's not even getting into the whole universe of religious groups gobbling up radio stations and taking over small-town movie theaters.

An additional question might be: can we save legacy media, and should we try? The public hasn't just lost faith in established news outlets because they can turn to the likes of Ben Shapiro or Joe Rogan instead. It's been a combination of factors, from the business model of media to the cost of subscriptions to the sort of elitist, horse-race type coverage so many outlets have provided over the years. Even as someone who believes fiercely in the value of news and that good journalism should be paid for, I'm butting up against my ability to be able to afford so many different paid subscriptions, never mind my desire to pay for and consume all of it. It makes me think of an interview I did with NYU media professor and critic Jay Rosen about a month before the first round of Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, in which he told me he worried about good journalism becoming something reserved for elites.

"For many, many people, whether something happened or not...is that completely irrelevant?" he wondered. "My own view is that journalism is gonna survive as a high trust product, and the breadth or narrowness of the market for that product will depend hugely on politics and culture, not just the performance of the press. So it'll always be there for a minority, especially people who can pay a lot, they will definitely have news. And the journalists who provide it to them will definitely ask, did this really happen or was it a right-wing fantasy? And that'll be foundational to how do they do their journalism. But not only will it be a minority product in the sense that a small market pays for it, but also the high price of the good will reflect how valuable it is for an elite only to have that knowledge...and the fewer people who are informed the better."

Plenty of mainstream or legacy outlets still have some credibility amongst a large percentage of the population, although Bezos seems to be doing his damndest to erode the credibility of The Washington Post as quickly as possible (was his purchase of that paper the most expensive catch-and-kill play ever? Maybe!). What would a systemic approach to fixing media look like? To preventing it from becoming this elitist product Rosen outlined? Hint: it does not look like finding "the Joe Rogan of the left" and funneling all the dollars in his (you know it's his) direction.

I know for climate reporters, many of us opted out of working for legacy media at some point or another because we simply were not allowed to do the sort of reporting we felt was important. That is especially true for those of us with an accountability focus. It wasn't because we wanted to do sloppy work, or because we were so ragingly biased we couldn't operate within the established media system, nor do I think being accessible and humorous is mutually exclusive with being rigorous. It was because we wanted to give people the information we thought they needed most and we were tired of being asked to trade in false equivalencies.

For research on my book (coming next year!), I took a couple of trips to an archive containing decades worth of records from the Atlas Network, a global network of more than 500 "free market" think tanks. One of the many interesting things I found there was a box labeled "Potential Intellectual Entrepreneurs." It was a fascinating window into how Atlas, which helped to start Donors Fund (often described as the right's "dark money ATM") and counts many of the organizations involved in Project 2025 as members, finds, cultivates, and sustains talent. Intake forms note whether the person in question has come to Atlas seeking a grant or been found by the organization's leadership or someone in their network. They note what sorts of things this person is doing, where they're located in the world, and what kind of support might make the most sense. Various other forms and reports track their progress, note connections that might be useful to them, ensure they're connected with the right funders and so forth. Several of the climate-denying reply guys I've been dealing with for more than 20 years were in there. While they were being supported throughout those decades, encouraged to keep doing and saying the same things over and over and over again, I have had to continuously prove myself, come up with new ideas and projects all the time, prove the value of journalism in general, produce projects for half the budget any other media house would and on and on. Why does "the left" require endless sacrifice while the right endlessly rewards any win? Another great question to be asking instead of "who is the Joe Rogan of the left?"

Instead of receiving the sort of committed, long-term backing that allows folks like Charlie Kirk or Jordan Peterson to thrive, churning out an unbelievable volume of content and leveraging technology (and relationships with tech platforms) to amplify it, independent creators are either constantly working on crowd-funding or caught in an endless cycle of grant applications and reporting, leaving us with less and less time to create content, less stability, and an increasing amount of legal and financial risk. How the fuck is anyone supposed to spend three hours a day smoking weed and engaging in "thought exercises" under those circumstances?

If you're wondering what this has to do with addressing the climate crisis, the answer is quite a bit. In its most recent report, the IPCC noted for the first time the role media plays in either driving or obstructing the political will required to act on climate. The media “shapes the public discourse about climate change and how to respond to it,” the report noted. And this “shaping” power can usefully build public support to accelerate climate mitigation – the efforts to reduce or prevent the emission of the greenhouse gases that are heating our planet – but it can also be used to do exactly the opposite, which is largely what’s been happening since the 1970s.

Lead author Max Boykoff, the researcher responsible for the IPCC’s increased understanding of the role of media in climate policy, told me the media plays a fundamental role in shaping both policymakers’ and the public’s understanding of climate issues. “People aren't picking up the IPCC report or peer-reviewed research to understand climate change,” he said. “People are reading about it in the news. That’s what shapes their understanding.”

These days they are also reading about it in newsletters, watching videos about it on YouTube or TikTok, and listening to podcasts about it, but more on that in a minute.

Technofascists have fully captured the information ecosystem.

If you have not read Cyberlibertarianism yet, I highly recommend doing so. And sorry but no, Technofeudalism—while a fine book and a decidedly shorter and easier read—is not cutting it. One was written by a tech guy turned academic who's been keyed into the technofascists and the threat they pose since the early aughts, the other by the former finance minister of Greece, for whom these dudes are a comparatively new phenomenon. (Relatedly, also highly recommend The Age of Surveillance Capitalism). A key theme Cyberlibertarianism raises is the regularity with which tech execs compare the advent of the Internet and social media to the arrival of the printing press, wrapping it in the same trappings of democratization as that storied machine and arguing that digital technology renders the press obsolete.

There are several handy tricks at play here, starting with the fact that digital media platforms are profit-making tools, not democracy-spreading tools. They were created by private corporations to gather intel on the public and sell it, to harness the attention garnered by digital content and monetize it, and to encourage the public to accept 24-hour surveillance. While the printing press led to an increase in propaganda simply by virtue of creating a means of production and distribution, digital platforms had fascist and propagandist goals from jump. Tech evangelists love to point to the use of Twitter by organizers of the Arab Spring protests as proof of their value as tools of democracy, and leave out the bit where it was also used to surveil and criminalize those organizers.

Today, Elon Musk fights against social media regulation as though the last remaining bulwark protecting free speech globally is the ability of tech companies to operate outside the law, with his de facto PR guy Michael Shellenberger claiming that even labeling information as "not vetted" is "censorship." The reality is if platforms like his can't operate with impunity as limitless cesspools of propaganda, they lose both financial and political value.

And then there's the simultaneous erosion of the press. It has always irked the tech gods and corporate executives alike that the only group that gets a special shout-out in the First Amendment is "the press." My longtime obsession, former Mobil VP Herb Schmertz, bitched about this constantly. He loved to threaten of "the public" rising up and stripping the press of its protections if it felt they weren't using their special privileges responsibly. Which is not to say that the press isn't or shouldn't be responsible to the public, just that Schmertz, as a key architect of corporate citizenship and the legal fight to secure rights for corporations, was primarily concerned with how the press was impacting his employer's bottom line not whether it was fulfilling its duty to voters.

So again, we have a systemic issue to tackle: what do we do about the fact that technofascists now control not only the dominant distribution mechanism for information, but also the algorithms that dictate who sees what? To place it within our Joe Rogan frame: How can the left make use of YouTube's algorithm the way the Joe Rogan Experience has? Although I'd argue that it's more important to reduce the power of the algorithm altogether, but hey you gotta start somewhere.

There are numerous ways to juice the algorithms, of course, and all of them cost money. There is a suite of necessary regulations that could help loosen the chokehold tech companies have on our information ecosystem, too, but at the moment only the European Union and Brazil are attempting to implement them.

Houston, We Have a Podcast Problem

I suppose it's surprising that I, a podcaster, am pointing out the obvious podcast problem here, but I have actually been squawking about this for quite some time. There's a reason the majority of those big red circles started their disinformation grift in podcasts (Rogan didn't start his career there, obviously, and is a bit different than the rest because he already had a large following when he started his podcast, thanks to previous careers as a failed comedian, Fear Factor host, and MMA announcer, but he did really start to lean into dis- and mis-information far more as a podcaster than he had previously.) And no, it's not just that having a podcast is like catnip for a certain type of white guy who crushed it in high school debate club. Again, there is a structural issue at play here that is being largely missed. And, to be fair, it's not just podcasts, newsletters fit in here too. In a nutshell: the Federal Communications Commission, the FCC, hasn't gotten around to regulating these new media forms, and may never.

Relatedly, the thing Musk keeps fighting against when he moans about the Digital Services Act in the EU, for example, or Brazil's "Internet Bill of Rights," is not actually censorship so much as it is the idea that social media should be subject to the same rules every other sort of media is. For its entire existence, this form of media has had all of the benefits of the media and none of the risks or responsibilities. As currently written and interpreted, Section 230 (of the Communications Decency Act), another thing you may have heard Musk and his crew ranting about, rids tech platforms of all liability for things said and done on their sites. Yet, from their very earliest days, these platforms have competed with news publishers—who carry enormous legal liabilities and risks—for not just eyeballs but, relatedly, ad dollars.

The agency overseeing digital advertising in the U.S. is the Federal Trade Commission, or FTC. Unlike the FCC, which is proactive about regulating advertising in traditional media forms, the FTC generally won’t investigate anything unless and until a complaint is made and even then an investigation is not guaranteed. The FTC has had “green guides” meant to protect the public from false environmental claims for more than 30 years, for example, but the first complaint ever filed against an oil company for violating those guidelines by greenwashing came in 2021 against Chevron. The complaint, jointly filed by Earthworks, Global Witness and Greenpeace USA, accused Chevron of several direct violations of the FTC’s Green Guides, including advertisements that, among other things, claimed Chevron produced “ever-cleaner” or “clean” energy, though the company was spending less than 0.2% of its capital expenditures on renewable energy sources. Ultimately the FTC declined to take any action. No wonder, then, that oil companies have rapidly increased their advertising across podcasts, newsletters, and social media over the past 5 years.

Ineffective as it is, at least there's some mechanism in place to deal with false advertising in podcasts, newsletters and social media. No such thing exists on the content side of the equation. While publishers have to carry liability insurance to cover errors and omissions, and are subject to defamation claims if they get a story egregiously wrong, Joe Rogan can get it wrong all day long with impunity. The one time Rogan was held to account for peddling falsehoods on his podcast, which he has done repeatedly over the years, was in response to an episode he ran during the Covid-19 pandemic with an anti-vax medical researcher. And there was no legal or regulatory action involved, it was just that Spotify responded to multiple podcasts and musicians leaving the service and various members of the public boycotting it, by taking down some episodes and committing to putting some kind of system in place for basic fact-checking on the show.

The most eye-popping example of this from newsletter land recently came by way of Michael Shellenberger, a long-time flak who anointed himself a "leading investigative journalist" after writing...one tweet thread as part of the Twitter Files "investigation." In his zeal to defend his new patron from the "censorship industrial complex," Shellenberger used his newsletter and large social media following to attack Musk's critics far and wide. In a post he wrote for his newsletter, Public, and later submitted to Congress as official testimony, Shellenberger and a colleague wrote an entire profile about Imran Ahmed, CEO of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, accusing Ahmed of being a spy while also confusing him for a convicted child sexual predator with a somewhat similar name (Imran Ahmad Khan). The mistake was raised to Shellenberger multiple times, including by Ahmed himself who raised it publicly shortly after the piece was published, and left unchanged on his website for more than a year (not to mention submitted to Congress as a matter of record) until Jesse Singal pointed it out in his newsletter late last year.

If The New York Times did such a thing, it would be sued for defamation and would have to prove that it took the necessary steps to avoid such a mistake and that it corrected the mistake as soon as it was raised. In other words, they would have to prove that they were not engaging in—my favorite legal term of all time—"actual malice." This is important for a few reasons. First, there's the obvious fact that being able to peddle falsehoods to millions of people with impunity is not great, nor is having zero recourse if someone blatantly defames you. Then there's the fact that the right is currently trying to make the risks even greater for traditional media at the same time that it leverages the total lack of regulation in digital media. For the past few years, rightwing think tanks have been floating the idea of chucking the "actual malice" test for libel, arguing that it lets the press off too easy. Justice Clarence Thomas echoed this call in 2023...right around the time ProPublica was poking into the many gifts he had inappropriately accepted while a Supreme Court Justice.

It's entirely conceivable that in the not-so-distant future the tech bros could win their war on the press, successfully stripping the press of its unique First Amendment protections while expanding the rights of corporations to lie, and the rights of right-wing "provocateurs" to defame and disinform with impunity in the digital sphere.

Joe Rogan is certainly emblematic of all of the above, but he's a symptom. Or to put it in tech speak, a bug. We need to be looking at the features, or really the whole operating system, not just a patch for that one pesky glitch.

Latest Climate Must-Reads (and Listens and Watches)

- [Film] 2073 - if it gives you anxiety to have all your worst fears about our current moment confirmed, skip this, but personally I was impressed by the breadth of knowledge in Asif Kapadia's sci-fi-documentary mashup, and by the creative approach overall.

- Trump Is Making Risky Bets in Pursuit of a Mining Boom, by Jael Holzman for Heatmap. One of the many big stories slipping through the cracks at the moment is the Trump administration's unhinged, no holds barred approach to mining (which seems at least in part driven by Trump's obsession with China). Thankfully Holzman is on it (as she has been for a while!)

- Heated, by Emily Atkin. Just a general shout-out to the OG of climate newsletters; I have been consistently finding Heated helpful when I'm feeling overwhelmed by the sheer volume of Trump news.

- "All Hell Breaks Loose: How Big Oil Ruined a Small Texas Town," by Alex Ip for The Xylom. This is a fascinating story about a high-income, ocean-front, majority white, conservative town in Texas that woke up one morning to discover it had become a fenceline community and the largest oil export hub in the country. (This one is the first of a three-part series).

- [Video] "How Oil Propaganda Sneaks into TV Shows," by Climate Town. Love the folks at Climate Town in general, and this episode really ties into what we're talking about above because it traces an unhinged anti-renewables rant in the show "Landman" back to the director's appearance on...what else? Joe Rogan's podcast.

- [Podcast] Malcolm Harris on the Radical, Liberating Possibilities of Realism, by Adam Lowenstein for Drilled. I know I'm biased because we ran this in Drilled, but Adam handed it over edited already and I enjoyed the heck out of listening to this conversation. If you prefer to read, you can check it out on our website here.

While you're here...it's getting harder and more expensive than ever to do the sort of reporting Drilled is known for. If you're able to support us, please consider either upgrading your subscription here (button below) or signing up for our Patreon. To thank you for your support, we'll be sharing episodes from our new season (on the Energy Transfer v Greenpeace suit, debuting June 3rd!) early with subscribers. We're also working on bonus subscriber content. We will never paywall our investigations; your support helps subsidize open access for all. Thank you!