Highlights from the House Oversight Committee's Climate Disinformation Documents

This fall the House Oversight Committee held its third hearing on climate disinformation. You can read more about the hearing itself here, but today I want to talk about a complement to it: the two rounds of documents the Committee has made publicly available from its subpoenas.

The New York Times published a story on the first batch that coincided with the hearing, and then a whole bunch of outlets published stories on the same documents the NYT mentioned, but there are more than 200 pages of internal emails and strategy memos here, and not all of it ended up in that one story! Last week, the second batch dropped and this time the Washington Post had the exclusive. But there were even more documents in that batch (more than 1000), so again, it's impossible to capture all the findings in a single news story. Or newsletter for that matter! I have a piece coming out in The Intercept this week with some analysis of these docs, but couldn't even come close to fitting it all in, so am sharing my notes on all 1500-ish pages with you here.

As someone who spends an inordinate amount of time reading PR strategy documents from 20, 50, even 100 years ago one thing these documents just scream to me is that this industry has not come up with a new idea on this stuff in a long time. In particular I saw echoes of our old friend longtime Mobil VP Herb Schmertz all over these.

Following are the things that jumped out at me, but I encourage folks to read it all for themselves here and here, and to check out Climate Files DocumentCloud for their annotated versions.

The industry's climate "solution" leans on getting the public to accept methane gas as a "green" fuel (or, barring that, at least a "bridge fuel") and building out enough carbon capture to make oil "low carbon."

The fossil fuel industry is once again pushing the idea that methane gas—a fossil fuel—is somehow an alternative to fossil fuels. The plan appears to be to lean on gas and carbon capture (which can magically make crude oil "low carbon,") and call it "transition."

The API is particularly keen to market "differentiated" or "responsible" natural gas, which includes renewable natural gas. We've covered this before, but renewable natural gas is an interesting one. It's made from captured methane, from either concentrated animal feed operations (CAFOs) or landfills, so the industry often describes it as "net zero" or "zero emissions," but that doesn't account for the emissions associated with actually using the stuff. The other issue critics of RNG often point to is that by even the most optimistic projections, RNG could only ever supply about 20% of energy demand, but it could help ensure that gas infrastructure stays in place for decades.

In a 2021 memo to the board, API notes:

"Differentiated, or "responsible" natural gas is becoming increasingly important to buyers in both domestic and international gas markets. API proposes supporting the ongoing development of markets for differentiated natural gas, recognizing the significance of these efforts in ensuring natural gas continues to be viewed as a major component of a lower carbon energy future."

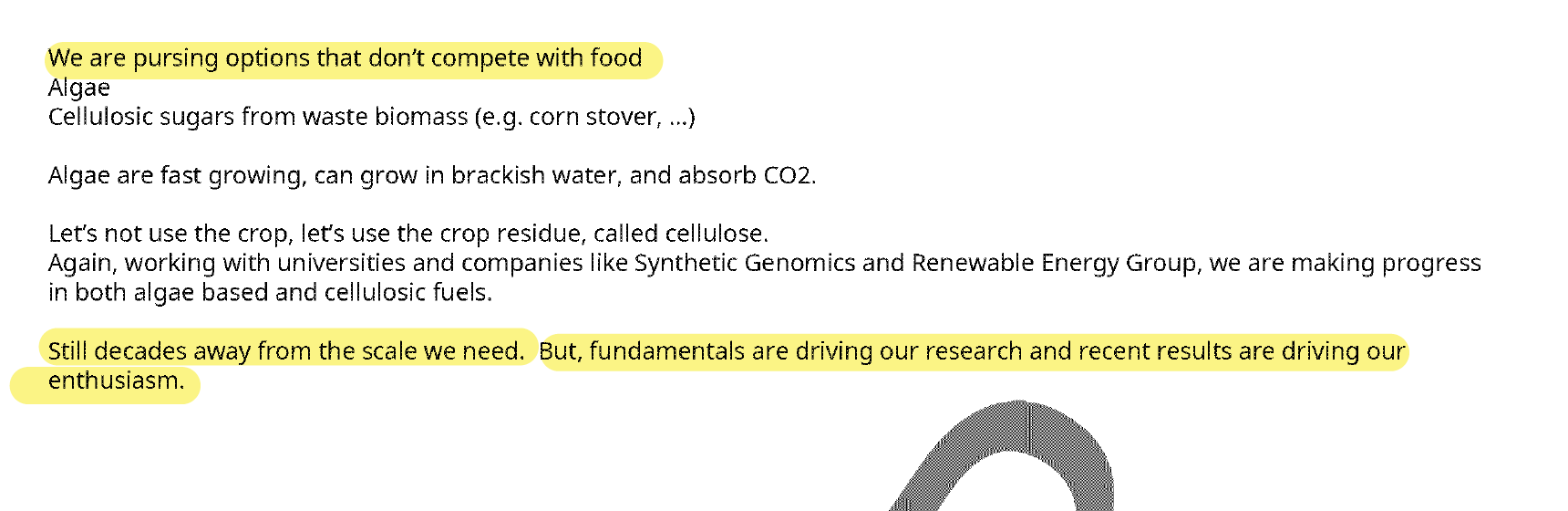

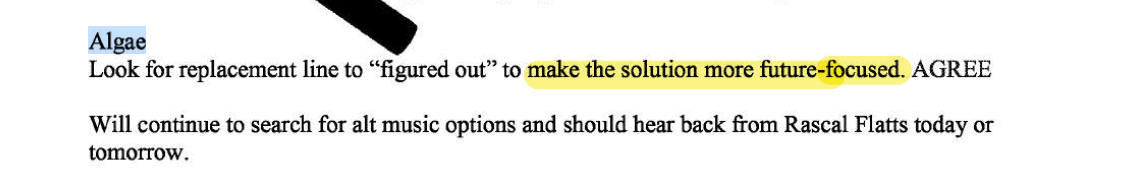

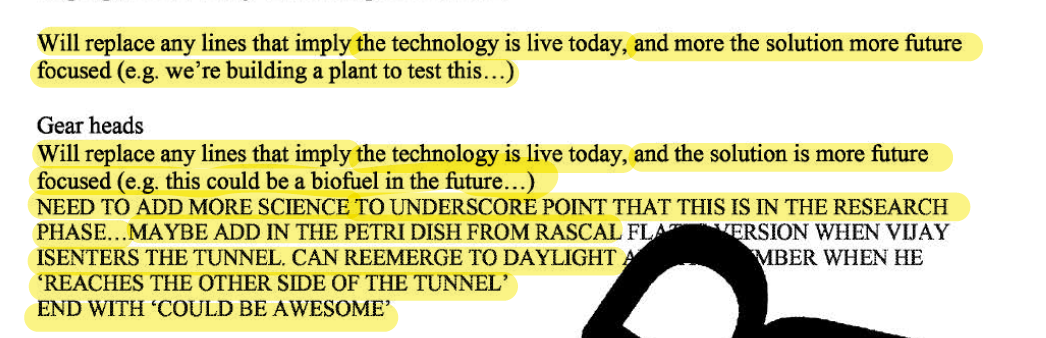

A handful of Exxon emails in which company executives are going back and forth with their advertising agencies about what they can and can't say about algae biofuels and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) provide some interesting insights into how viable the company views these technologies to be. Creatives are encouraged to "make the solutions more future focused" as opposed to things that have already been figured out. On biofuels, they're cautioned that we're "still decades away from the scale we need." The feedback on an ad about CCS, a technology that the industry regularly paints as a fully operational tool is:

"replace any lines that imply the technology is live today, and make the solution more future focused (e.g. we're building a plant to test this ... )"

The resulting ads are technically accurate (and, importantly, legal), but nonetheless give the impression that these are real solutions. It's a behind-the-scenes look at how Exxon pulls off what's called "paltering," a technique climate disinfo expert John Cook has written about extensively.

Throughout these documents there's a real sense of urgency around securing a future for gas and scaling up carbon capture before it's too late. In a 2017 document outlining the potential for CCS on the Gulf Coast, for example, Shell notes that "the window for CCS to remain relevant with governments and society is closing quickly and action needs to occur within the next decade."

Once Again, With Feeling: Net Zero Is Not Zero

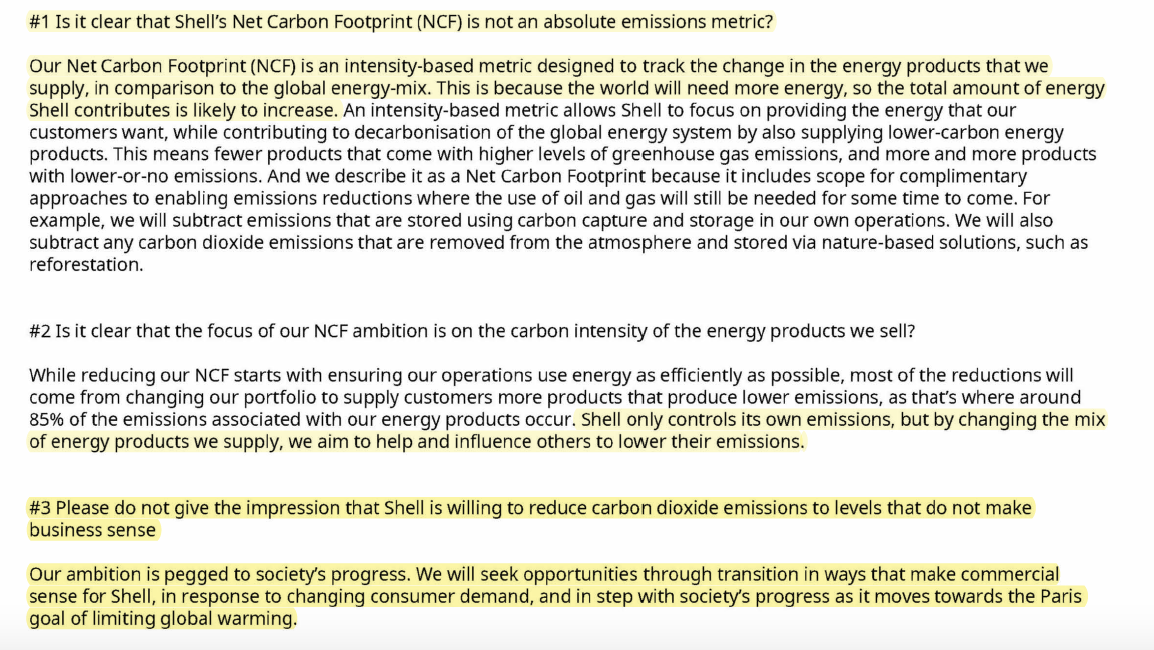

In case anyone was still under the impression that "net zero" is anything more than a marketing ploy, discussions amongst Shell execs about the company' Net Climate Footprint campaign should remove all doubt. In one email in particular employees are cautioned: "Please do not give the impression that Shell is willing to reduce carbon dioxide emissions to levels that do not make business sense."

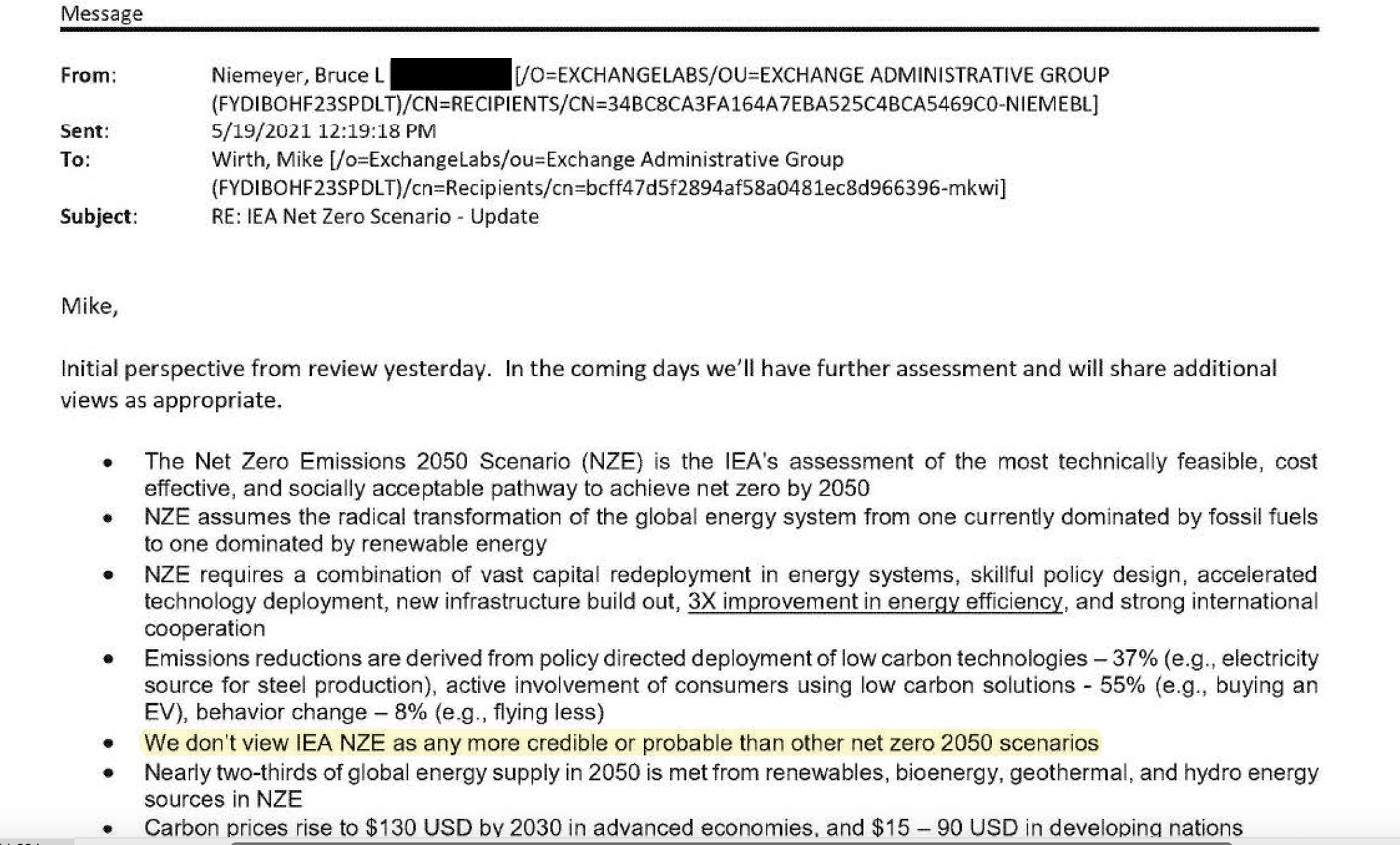

Shell makes it clear that it's not talking about actual emissions reductions, but rather "carbon intensity," a term that, like net zero, means almost nothing and is audited by no one, but sounds like it's doing something. Chevron is also in a hurry to leave "net zero" in its review mirror and embrace "carbon intensity". In an email to CEO Mike Wirth with his initial thoughts on the International Energy Agency's Net Zero Emissions 2050 Scenario (released in 2021), Bruce Niemeyer, President of Chevron's Americas Exploration and Production division wrote: "We don't view IEA NZE as any more credible or probable than other net zero 2050 scenarios."

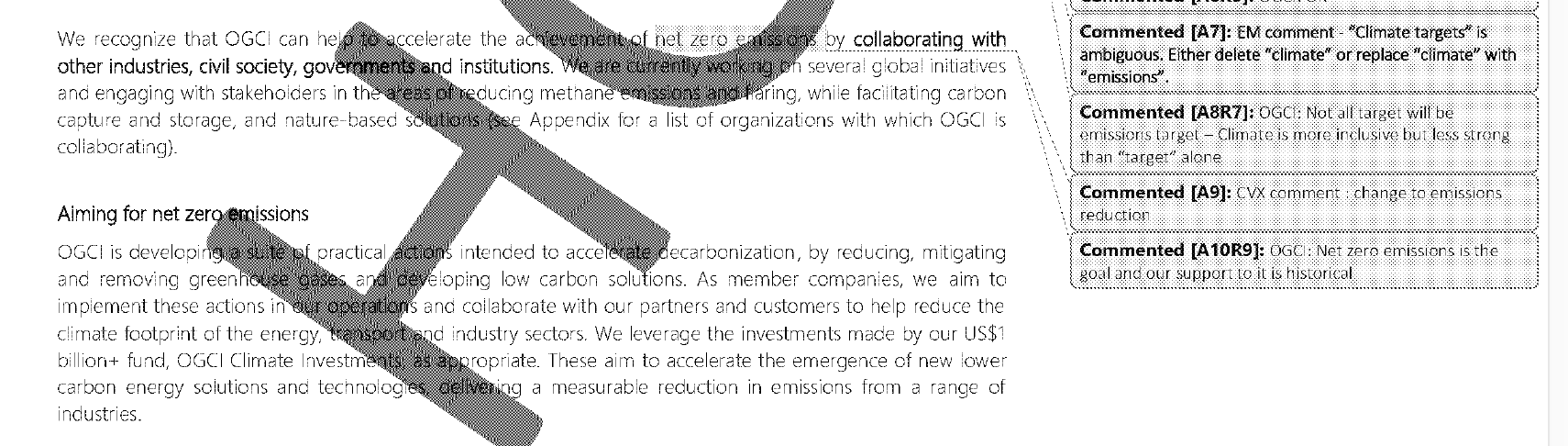

To its credit, Chevron has at least tried to stop making blanket net zero promises in public, preferring instead to only mention net zero with respect to its operational emissions, and to focus more broadly on "carbon intensity." In a document from the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative in which the oil majors are weighing in on how to talk about climate commitments and carbon capture, Chevron suggests changing "net zero" to "reducing emissions," only to be scolded by OGCI that the group has already committed to net zero in the past.

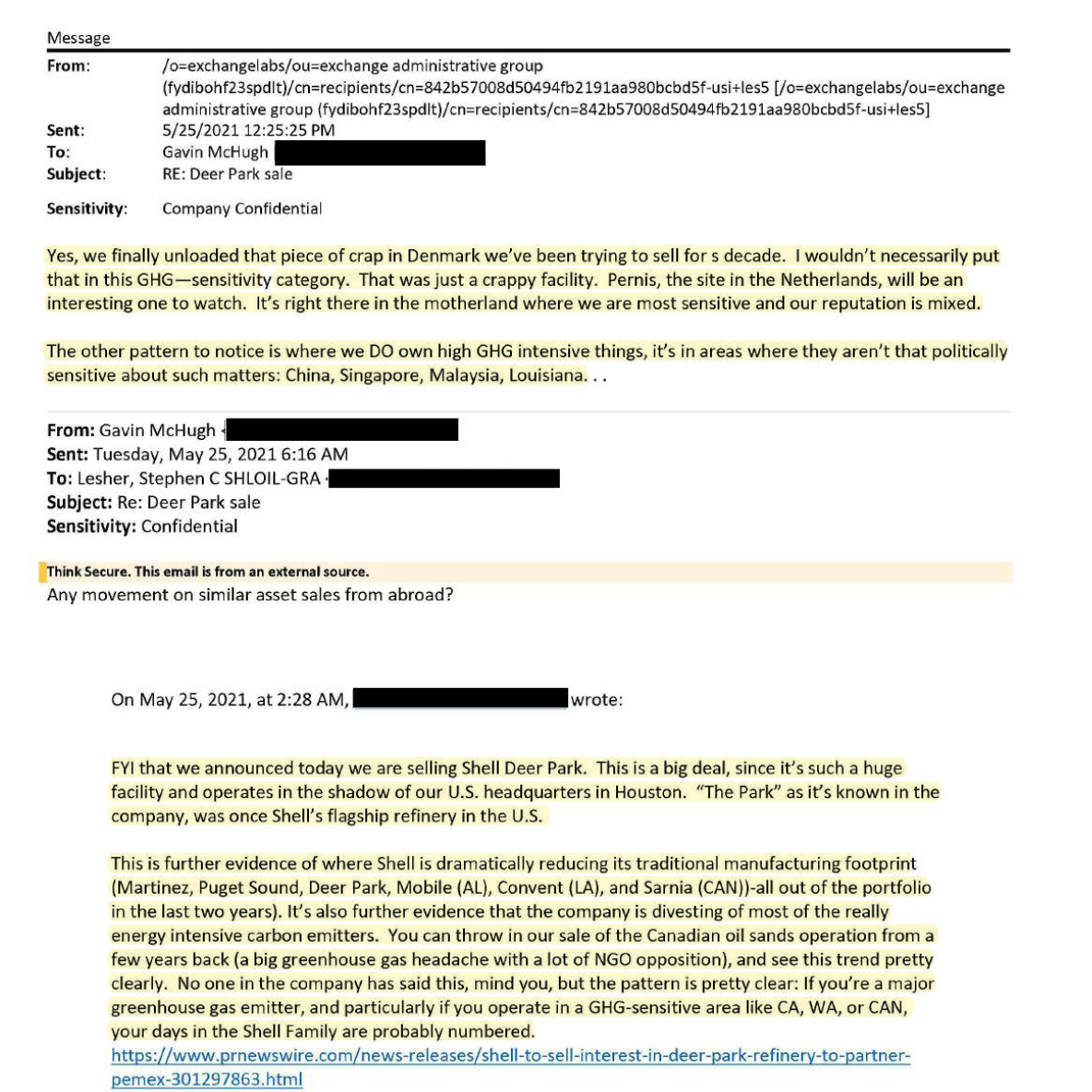

They Will Pollute Where They Want to Pollute

An email exchange between Shell executives about which facilities to offload says a lot about where the company thinks it's okay to pollute: anywhere that will let it. "Yes, we finally unloaded that piece of crap in Denmark we've been trying to sell for a decade. I wouldn't necessarily put that in this GHG-sensitivity category. That was just a crappy facility. Pernis, the site in the Netherlands, will be an interesting one to watch. It's right there in the motherland where we are most sensitive and our reputation is mixed.The other pattern to notice is where we DO own high GHG intensive things, it's in areas where they aren't that politically sensitive about such matters: China, Singapore, Malaysia, Louisiana."

And later: "No one in the company has said this, mind you, but the pattern is pretty clear: If you're a major greenhouse gas emitter, and particularly if you operate in a GHG-sensitive area like CA, WA, or CAN, your days in the Shell Family are probably numbered."

Relatedly, in the second document release, there are emails between Shell executives making it clear that these facilities are not being shut down or decommissioned, in other words the emissions associated with them are not being eliminated in general, they're just being removed from Shell's books. When pressured about the fact that selling polluting assets wouldn’t actually reduce emissions, a Shell executive wrote, “what exactly are we supposed to do instead of divesting…pour concrete over the oil sands and burn the deed to the land so no one can buy them?”

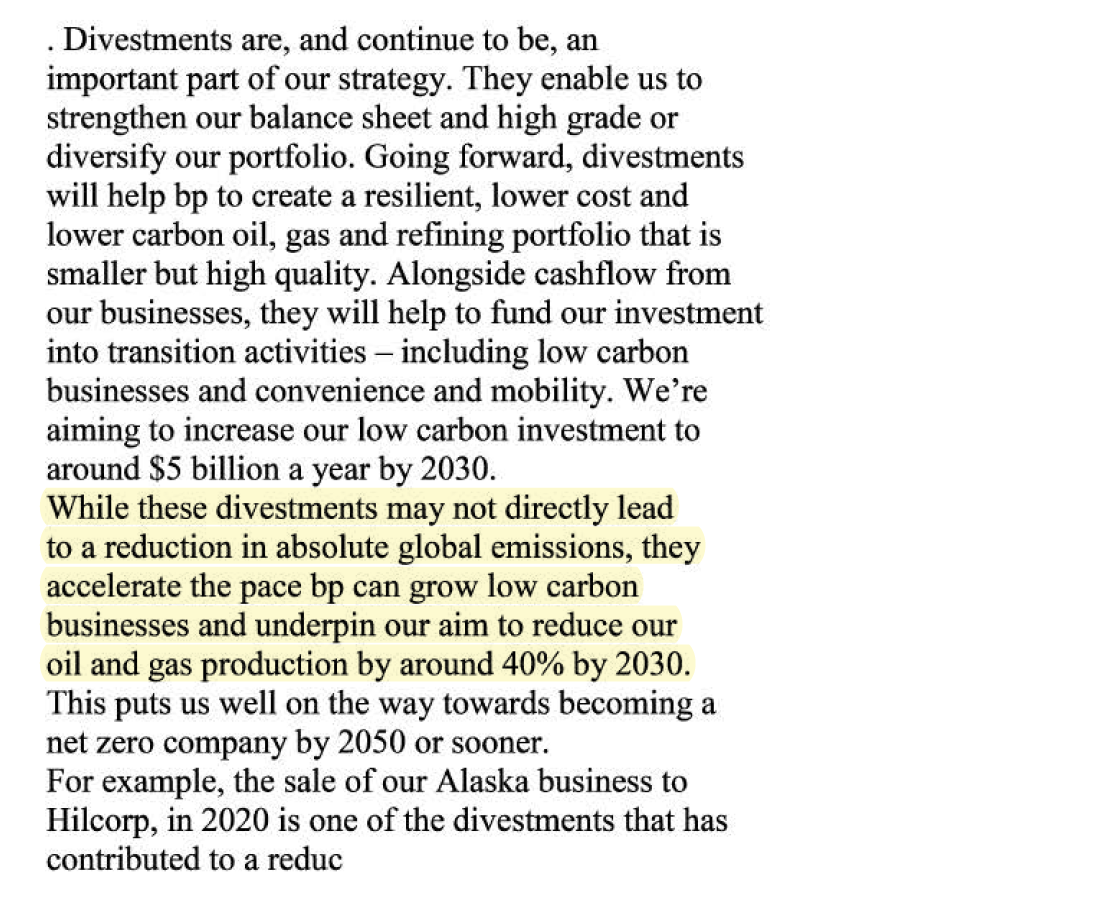

There are similar email exchanges between BP executives, in which they admit that offloading fossil fuel assets is an “important part of our strategy” even though these “divestments may not directly lead to a reduction in absolute global emissions.”

ExxonMobil Still Plays a Leadership Role in the American Petroleum Institute

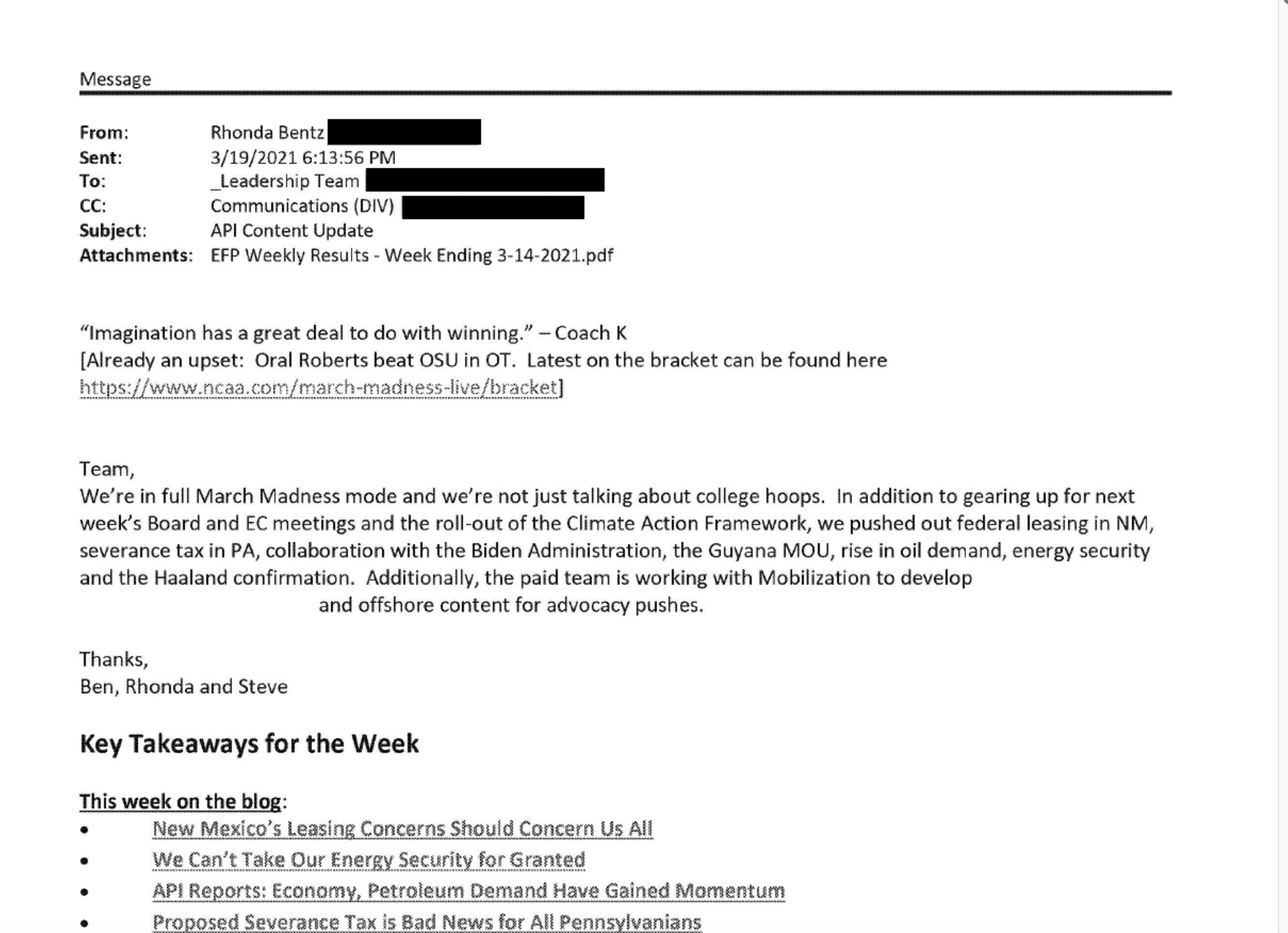

The American Petroleum Institute receives more of ExxonMobil's lobbying dollars than any other entity, and it shows. In an email updating members about the implementation of the API's new "Climate Action Framework," for example, former VP of Public Affairs Rhonda Bentz lists off the various things her team is promoting, including several expected, industry-wide items like "collaboration with the Biden administration," "rise in oil demand," and "energy security," but right in the middle is an item that really only Exxon cares about: Guyana MoU, a reference to the contract between ExxonMobil and the government of Guyana, home to one of Exxon's largest drilling projects, which could be producing close to 25% of its global oil barrels by 2030.

Oil Companies Gave Up on 1.5C as a Goal Way Before Anyone Else Did

While the rest of the world has only just begun to acknowledge this year that limiting warming to 1.5 degrees is unlikely to happen, turns out the oil companies—all of which supposedly support the Paris Climate Agreement and its 1.5C limit—were always shooting for 2C. BP was talking about 2C warming as the goal as early as 2017. Chevron had officially skipped past 1.5C as of 2020.

Partners = Pawns

Whether it's Princeton University or the Environmental Defense Fund, when a fossil fuel company invests in a partnership, they're not nearly as interested in your knowledge or research as they are in your power to influence others. And their power to influence you. An email from BP's former Vice President & Head of Regulatory Advocacy & Policy Bob Stout, about the company's funding of research at Princeton University, lays out the real benefit of the partnership: "I would only add that in addition to the value in informing our understanding of climate science and policy," he writes. "These relationships (along with those we have with Harvard, Tufts and Columbia) are key parts of our long-term relationship-building and outreach to policy makers and influencers in the US and globally….We do not always agree on matters of policy, but we do get valuable intel on the evolving perspectives and priorities of the environmental community and are able to tell the story of what we are doing and why in a more personal and compelling way."

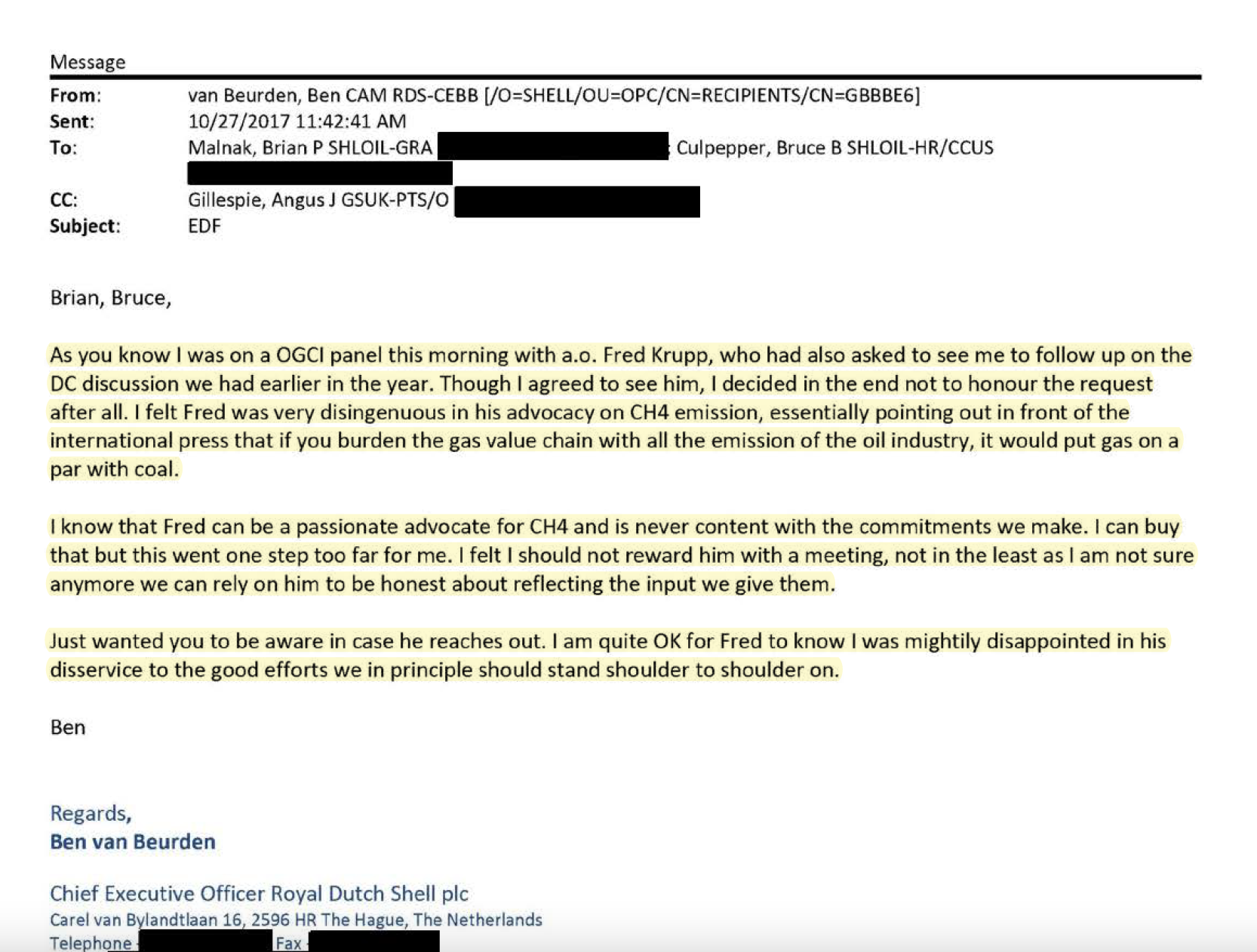

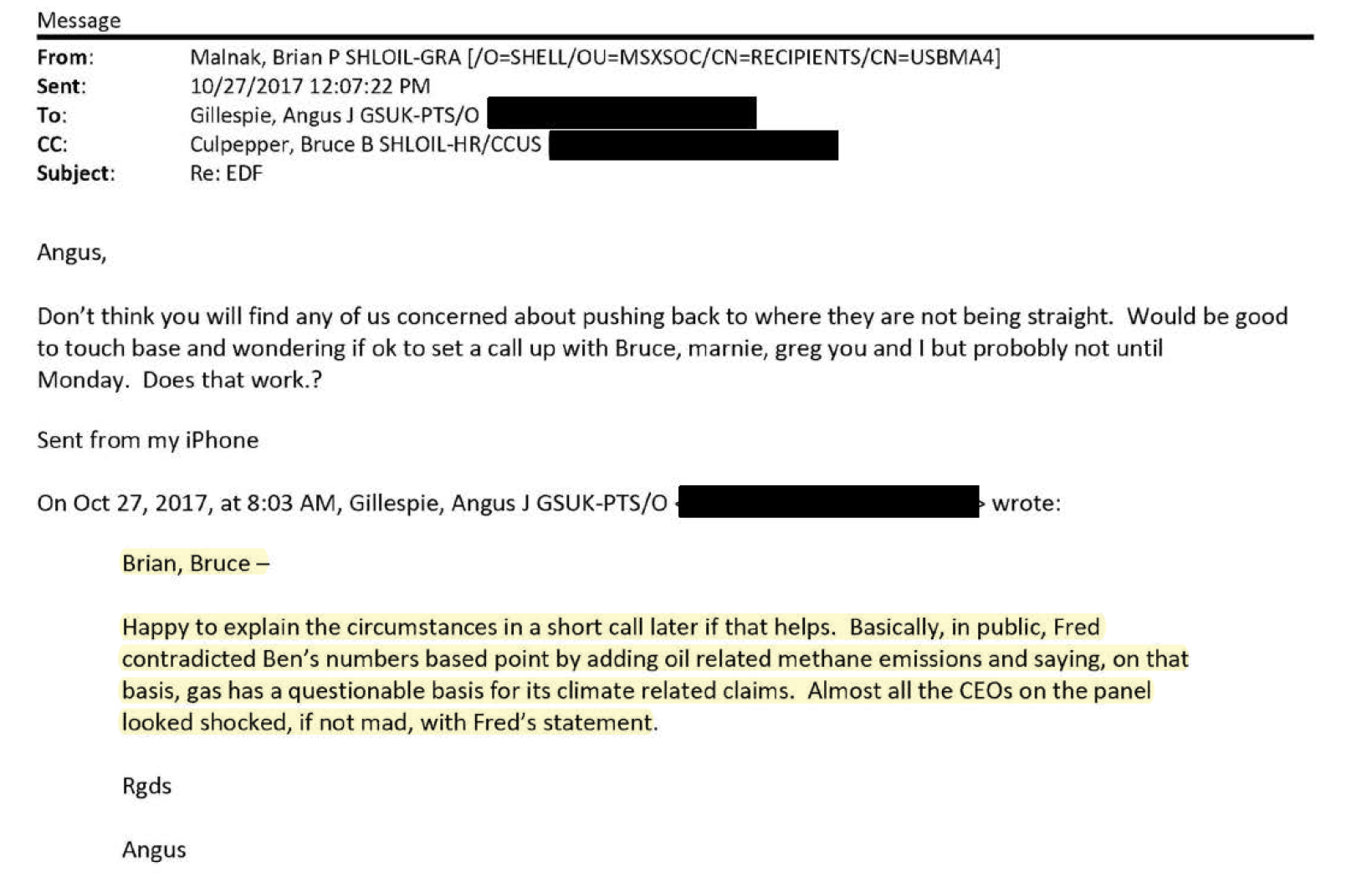

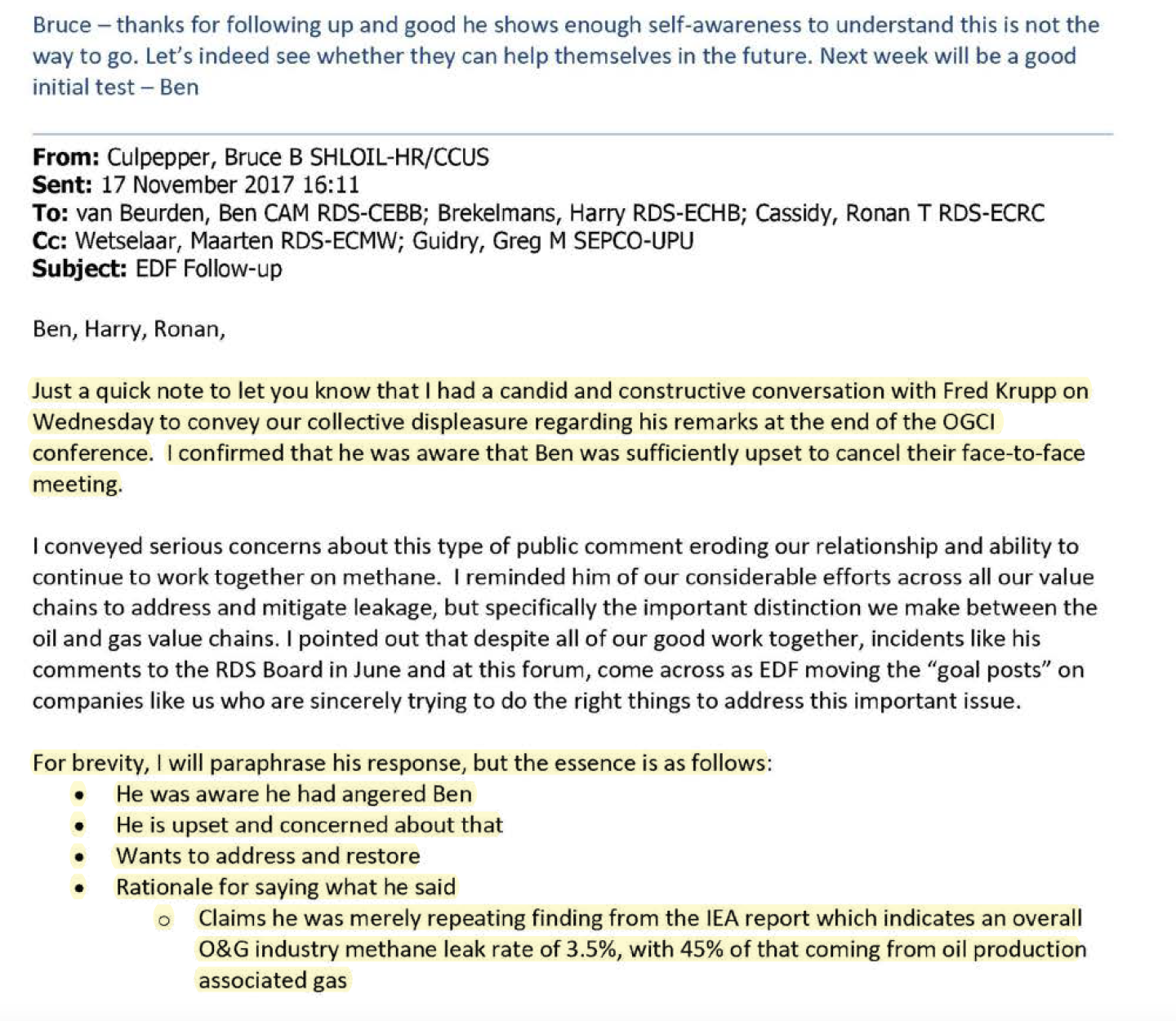

On the NGO side, a dust-up between Environmental Defense Fund president Fred Krupp and Shell CEO Ben Van Beurden makes it clear what sorts of strings a big donation from an oil major comes with.

The Art of "Creative Confrontation" Is Alive and Well

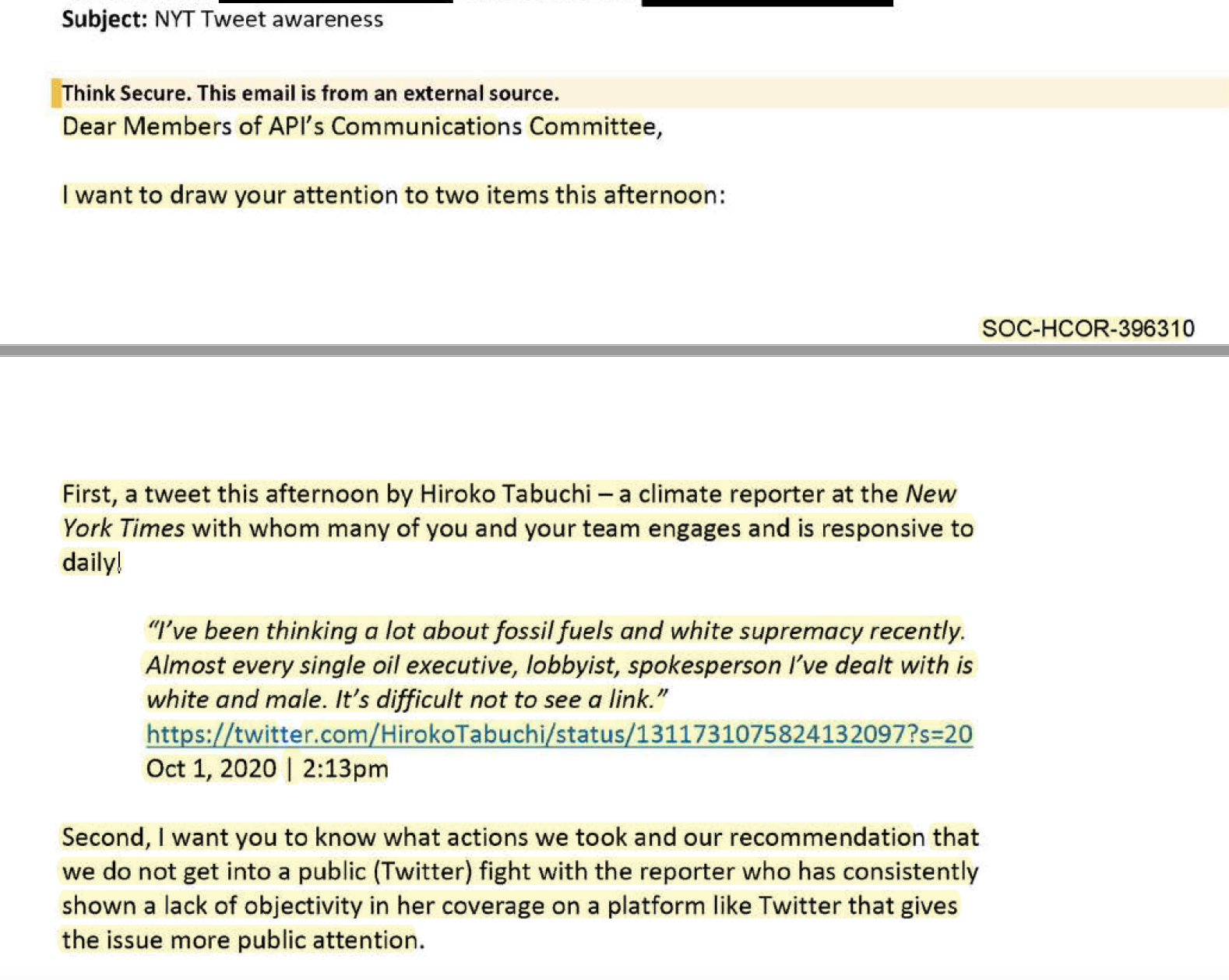

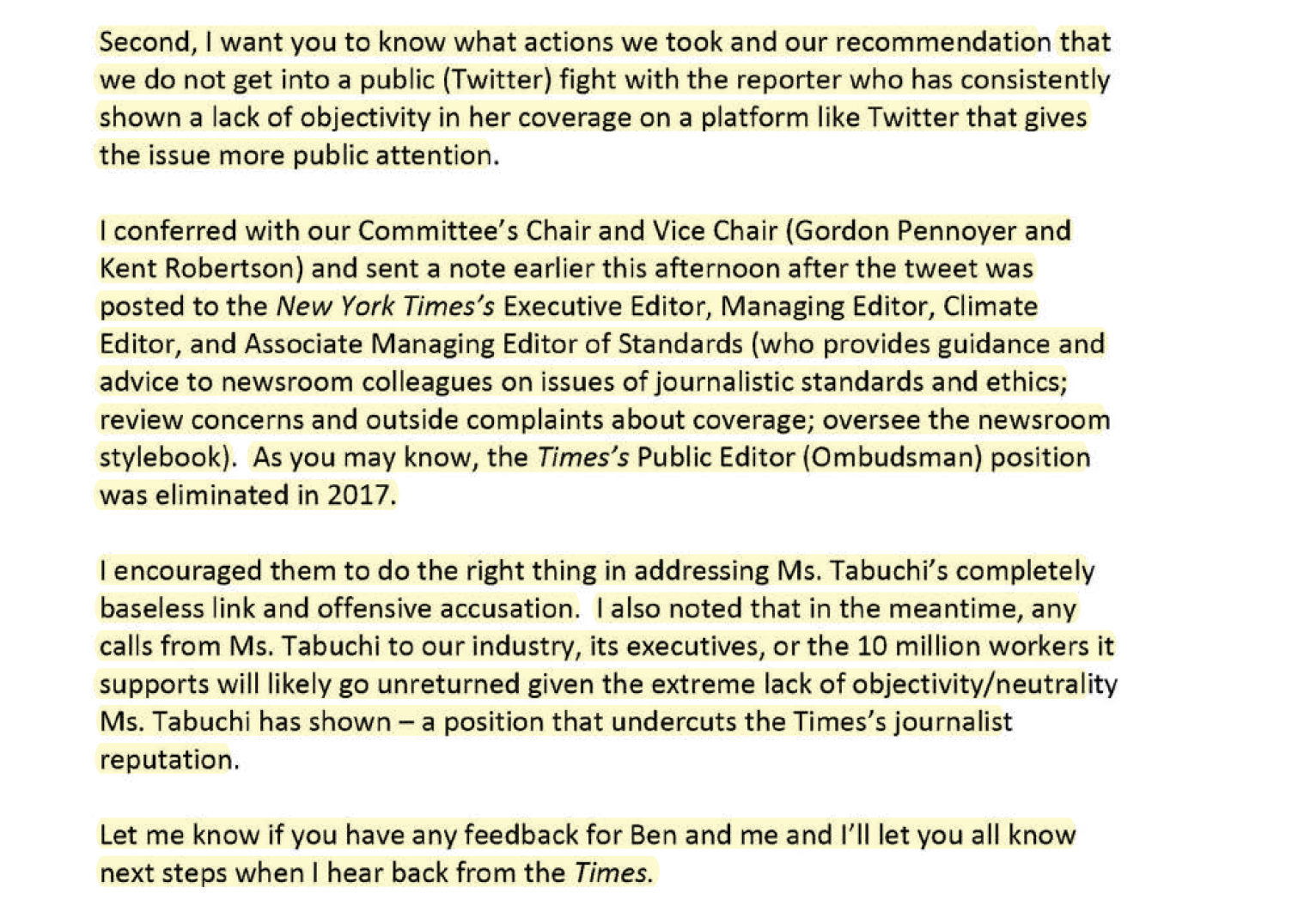

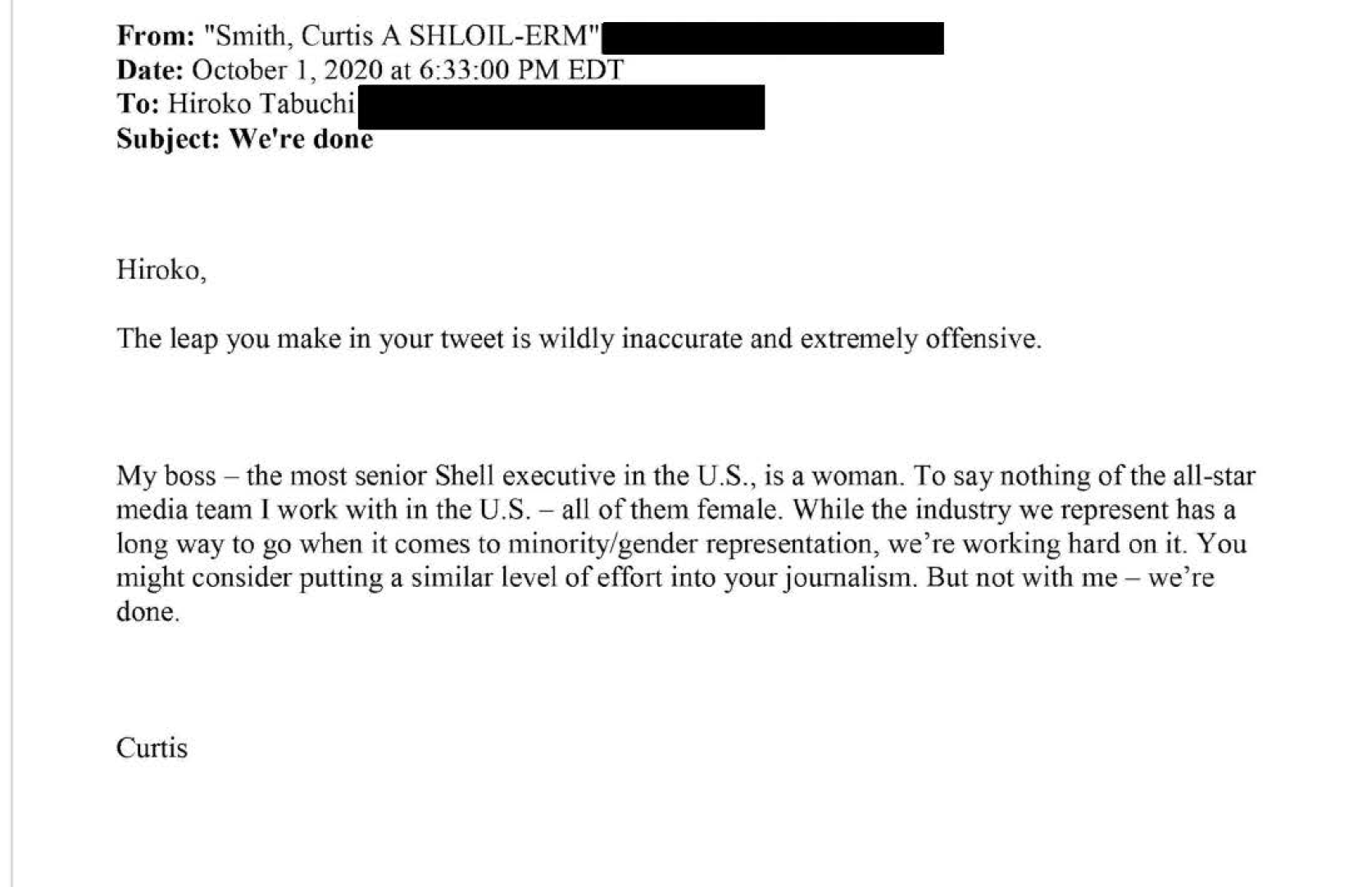

Back in the 1970s, legendary Mobil VP Herb Schmertz pioneered the art of bullying journalists or, as he called it, "creative confrontation." If journalists weren't covering Mobil's point of view, or he thought they were being too critical of Mobil, he called them up and let them know. And he let their bosses, and their bosses' bosses know too. Sometimes he threatened to pull advertising. Once he cut The Wall Street Journal off from any information at all—press releases, comments from executives, even quarterly earnings reports. It looked exactly like what the American Petroleum Institute and Shell tried to do to Hiroko Tabuchi, the New York Times's climate accountability reporter, once in response to a (now-deleted) tweet in which she referenced the shared history of the fossil fuel industry and white supremacy, and again in response to a story about the American Chemistry Council, which counts several oil majors as members, lobbying against regulations in Kenya that would limit the ability of American companies to sell single-use disposable plastic there. If it were only a group of smug flaks congratulating themselves for sending "nastygrams" and saying things like "Let's work on taking away their birthdays next," it would be easy to dismiss as clownish theatrics. But there's quite a bit of evidence that it works. Not just in the 70s and 80s, but today. After telling Tabuchi, in response to her tweet, "we're done," Shell publicist Curtis Smith forwarded his email to her colleague, Clifford Kraus, who he obviously considers a friend, with a note, to which Kraus replied "I obviously can't comment, but you wrote what you felt and that is good."

Rep Ro Khana (D-Ca), who co-chairs the committee and helped spearhead the investigation, thinks it also worked to pull Tabuchi off of certain types of climate stories. After covering the Committee's hearings on climate disinformation for a year, he says, "Hiroko's not covering it anymore. She's been taken off. So, you know, unfortunately, Big Oil succeeds sometimes when they engage in this kind of bullying."

What this exchange also reveals is the extent to which the API coordinates not just messaging strategy, but also execution, for the industry. After instructing the communications directors for all the oil majors not to engage with Tabuchi on Twitter, Meg Bloomgren, API's senior vice president of communications, explains that she has sent emails to three of Tabuchi's bosses, as well as to the Associate Managing Editor of Standards, about her conduct.

"I encouraged them to do the right thing in addressing Ms. Tabuchi's completely

baseless link and offensive accusation," Bloomgren writes. "I also noted that in the meantime, any calls from Ms. Tabuchi to our industry, its executives, or the 10 million workers it supports will likely go unreturned." It's a move straight out of the Schmertz playbook.

Social license to operate is still a big priority

It often seems as though the fossil fuel industry thinks of itself as above the law and endlessly powerful, but several of these emails highlight how much the industry still invests in maintaining a "social license to operate," a tacit acknowledgement from the public that it delivers enough benefit to society to warrant putting up with things like air pollution and spills and climate change. "While this patchwork of policies and markets creates challenges for a coordinated US energy transition," one document reads, "it also creates opportunities for an integrated, respected and credible energy company like Shell to take on an increased leadership role to shape effective policy at multiple levels in the transition, while maintaining a strong societal license to operate."

Another notes:

"While Shell is a leader amongst its US peers, our industry continues to have low credibility and trust with specific stakeholder groups (Energy Engaged audiences), amidst rising societal expectations on climate action."

And one of the key parts of Shell's U.S. Reputation Plan: is to secure partnerships "with credible external influencers and commercial entities that support and strengthen societal license to operate and grow at country and asset level;"

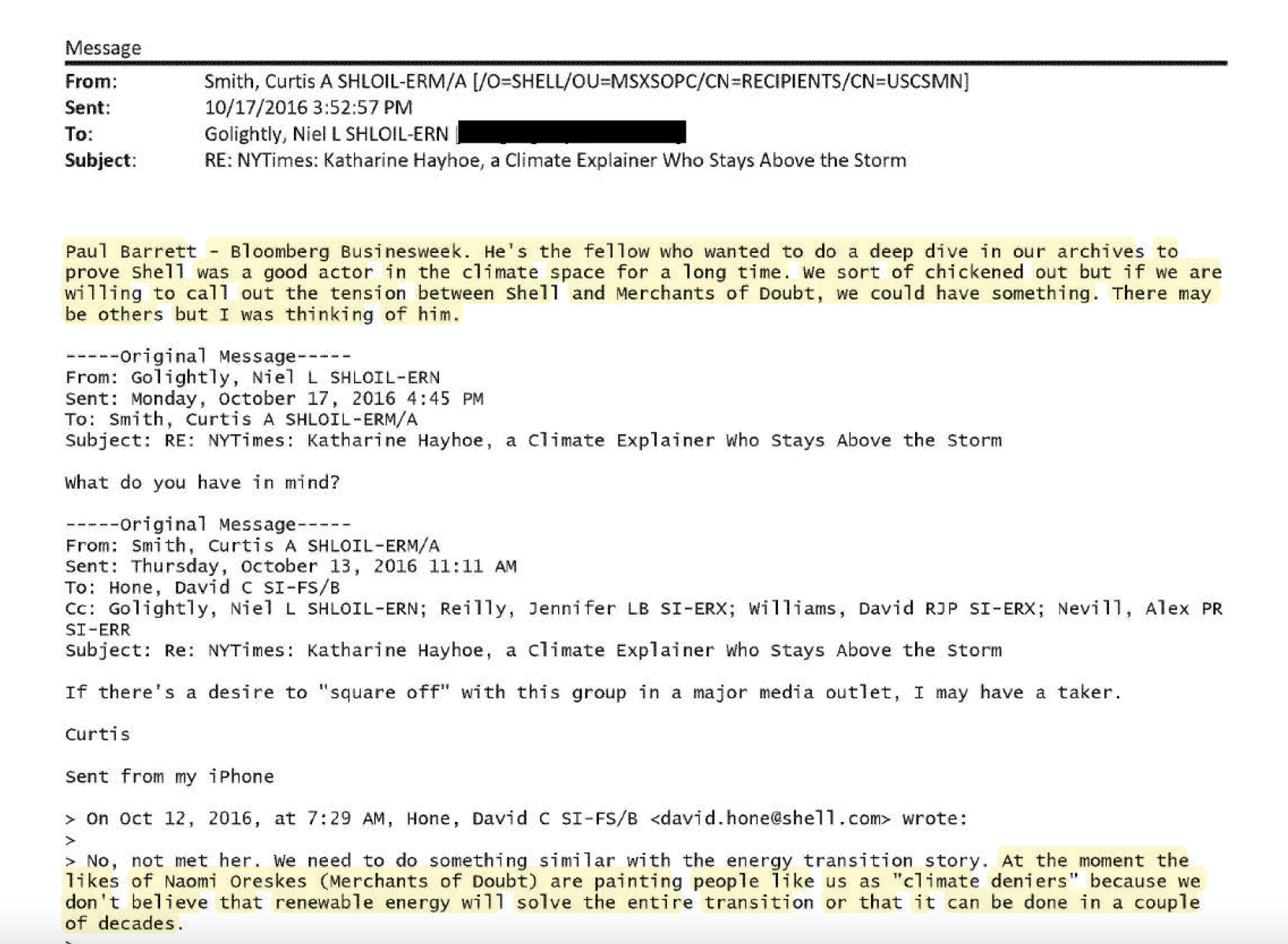

One such influencer they suggest by name is Paul Barrett, a former columnist for Bloomberg Businesweek who's now

"He's the fellow who wanted to do a deep dive in our archives to prove Shell was a good actor in the climate space for a long time," one email notes. "We sort of chickened out but if we are willing to call out the tension between Shell and the Merchants of Doubt, we could have something."

It's entirely possible Barrett was framing his request to access the archive in this way solely to gain access, but irrespective of what was going on there, it's interesting that Shell seeks to differentiate itself from the rest of the pack on climate. This comes up in emails about whether or not to partner with ExxonMobil as well, given the "reputational risk."