Podcast: How to Combat Climate Disinformation Around COP27

Next month, the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP), the annual UN Climate Negotiations Conference, will kick off in Cairo, Egypt. Once again, negotiators and politicians from all over the world will join up to talk through what they're willing to do to stave off human extinction. That sounds dramatic, right?

But that's kind of what we're talking about here. There will be the usual massive contingent from the fossil fuel industry there as well. Last time, in Glasgow, the fossil fuel industry sent more representatives than any one country did. And there's likely to be more of the same in Egypt. The organizers have, in a much publicized and criticized move, allowed major global polluter Coca-Cola to sponsor the event.

Even worse, they've also hired Coca-Cola's publicist, Hill & Knowlton, to do PR for the conference. If you missed season three of Drilled, go back and listen. We did an entire episode on Hill and Knowlton founder John Hill and his work for both the oil industry and the tobacco industry all at the same time.

Hill masterminded the strategy of hiring scientists to say tobacco smoking wasn't bad for you and that the jury was still out on whether it caused cancer. At the very same time, his firm was working for the American Petroleum Institute and some of its member companies. In fact, it was Hill who brought tobacco folks into the American Petroleum Institute. The longstanding relationship between oil and tobacco eventually resulted in the creation of the cigarette filter—a money maker for oil and gas companies looking for a new place to sell petrochemicals and a slight of hand for the tobacco industry looking to convince consumers that they could make smoking less harmful by smoking lighter, filtered cigarettes.

Hill represented Monsanto around the same time too, so no surprise that the chemical industry embraced a lot of the same tactics. Definitely the folks you want strategizing the messaging for your climate conference! I'm sure they won't be reporting directly back to their clients. Cue head banging against wall video.

At any rate, COP isn't just a time for official corporate greenwashing. It's also a period of time that tends to see major spikes in climate disinformation. Social media will almost assuredly be flooded with various memes about the elitists at COP, the failures of renewable energy, and that damn frozen windmill picture that makes the rounds every couple of years.

A coalition of environmental groups has come together under the banner of Climate Action Against Disinformation to monitor the disinformation that spawns around some of these big inflection points. They initially got organized around COP 26 in Glasgow, and now in advance of COP 27 in Cairo, they've put together a report full of information aimed at helping journalists and other communicators avoid unintentionally spreading or amplifying mis- and disinformation.

The lead author on that report, Connor Gibson, walked me through it.

"A little bit more savvyness is needed in newsrooms in the modern era in order to not allow that to happen, because certainly disinformers now know how to exploit that tension between editors and journalists in terms of something like viral sloganeering," he told me, talking about how common it is that journalists need to fight within their own newsrooms against some of the bad habits that spread disinformation.

"Climate Gate is the example that I use in this report," he says. "You know, how many major news outlets printed the word ClimateGate? That is the tagline of the climate change denial movement, and just putting that in your headline over and over really created a sense among news readers that there was guilt and that there was fabrication of data and all of the false accusations that had been made after those climate scientist emails were hacked and taken outta context and released. And you know, the fact checking that came after the investigations and exonerations that came after that didn't spread, that didn't spread nearly as widely as the phrase ClimateGate."

It never does. And that's the sort of thing this report hopes to help journalists avoid doing, but Gibson and the rest of CAAD are well aware of the biggest obstacle in tackling disinformation in general, and climate disinfo in particular: the lack of investment in journalism.

"I think one of the biggest insurmountable feeling trends that I looked at in this report is just the economics of the newsroom. You know, when there is a revenue incentive that is based around clicks, shares, most emailed articles that precludes the type of tone that is actually to stop misinformation from festering. And so the simple capitalist economics of keeping a news outlet functioning actually creates a breeding ground for misinformation as well, and is something that needs to be taken a lot more seriously than it currently is. But unfortunately, because it's about economics, I think that is one of the biggest obstacles that reporters will face when it comes to that tension between the responsibility of a reporter to communicate something accurately without feeding into conspiracy theory or myth, and the responsibility of an editor to keep the newspaper in circulation and financially healthy.

That's especially true in the years since social media changed the news business. It's increasingly common to see social media promotion that is, itself, wildly misleading even if the article it's promoting isn't.

This report draws on years' worth of research on psychology-based communication techniques from experts like Stephan Lewandowsky and John Cook, and a lot of the collaborators on reports like The Debunking Handbook and The Conspiracy Theory Handbook, as well as guidelines from civil society organizations like First Draft, the Data and Society Research Institute, and the Union of Concerned Scientists.

"These folks are really experts on helping people avoid the most basic traps, and this stuff has been around for decades, right? Like Richard Nixon, I'm not a crook. Everybody hears the word crook, right?" Gibson explains. "Or George Lakoff wrote the book Don't Think of an Elephant! because the only word that sticks in your brain after you say that is the word elephant."

A lot of this stuff has been known for a long time, but Gibson poked around at some headlines from major outlets, and found the same old mistakes happening.

"It's not because people are foolish, it's just there is an amount of faith in the audience when it comes to an honest journalist and editor writing a report and writing a headline that unfortunately just misses the traps that disinformation relies on in order to spread," he says.

"And that's gotta be really frustrating when you're a professional who writes something that's very intellectually honest and yet, it helps misinformation and disinformation spread. So that's really why we wrote this report."

Gibson says climate journalists were a key target not just because climate disinformation is on the rise and COP tends to bring big waves of it, but also because they dealt with disinformation before any other type of journalist. "The phenomenon of climate change denial I think has made climate change reporters a little more sophisticated in understanding these trends before social media made disinformation such a rampant problem in the last few years," he says. "And just the, the relentless nature in which that community of climate change deniers, you know, has stayed organized. So I would say that most of the people who are in climate reporting are far more sophisticated now than certainly they were in the 1990s or the 2000s when that phenomenon was a little underreported and the cast of characters wasn't as widely known."

"So, you know, we tried to write this report and publish it with acknowledgement that we're not writing it because climate reporters are particularly gullible or anything like that," he continues. "We think it's one of the more relevant fields with which to understand what communication techniques are required in order to mitigate misinformation and disinformation as well as a field where some of that understanding is already a little bit there."

Here are a few key highlights:

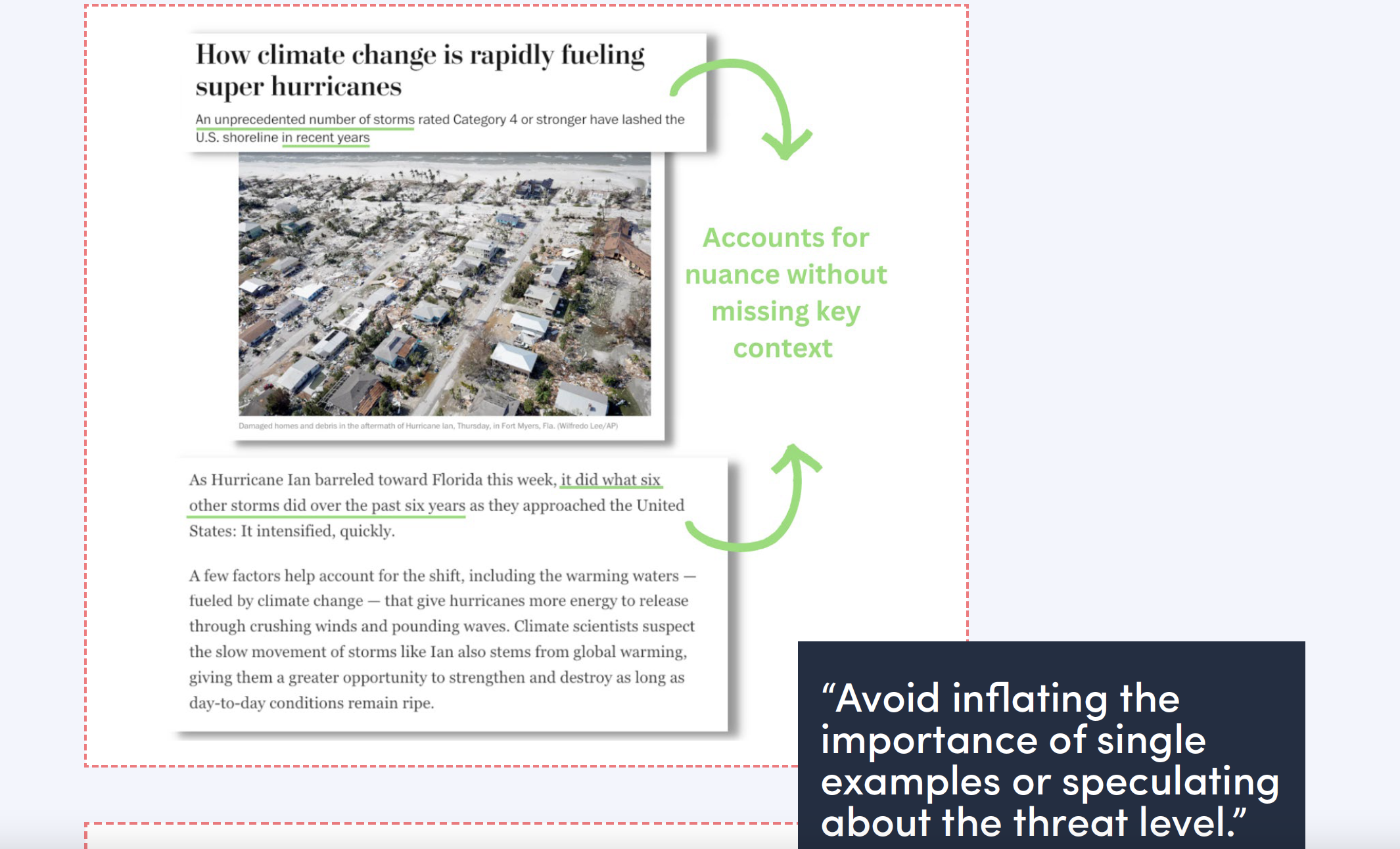

It's Time to Update How We Talk About Hurricanes

Hurricane science continues to develop, but by and large the media has not kept up. We are now at a point where scientists are more able to estimate how much worse hurricanes are as a result of ocean temperatures being warmer as a result of sea level rise and what that means for storm surge. That's not something scientists could do ten years ago. Even five years ago it wasn't as solid as it is today.

"There are very specific factors, which scientists clearly understand, that make hurricanes stronger, make them hit harder, make them cause more damage and suffering, and, and that is a nuance that can be navigated," Gibson says. The report gives the example of a Washington Post article doing a good job talking about climate change in hurricanes without losing track of either the nuance around the natural variability of weather or the realities of on-the-ground suffering in the wake of a hurricane.

Write Headlines that Omit the Disinformation

This is something that I see happening all the time, and partly, again, because of the economics of news these days. If something is controversial and trending, then there's a desire to capitalize on that by sticking it in the headline, but Gibson says that's one of the primary ways disinformation is amplified. "This brings us back to the classic Richard Nixon 'I'm not a crook example,'" he says. "Everybody heard him basically admitting he was a crook because that's how psychology works. You don't want to use the words that you do not want to stick in people's mind. That's just how our brains work."

Surprisingly, one of the worst offenders on this front is PolitiFact. "This is not intended to shame anybody, but the PolitiFact website kind of does not adhere to best practices when it comes to this. They quote the myth that they are debunking. So even when they have these really great images, including the pants on Fire, logo, the reality is that they are still quoting the myth at the top of their article, and then oftentimes the next thing is they use the word no and then they refute the myth. Again, that's two rounds of uplifting misleading language before getting to the nuances of their fact check.

Fact-Checking Is Key

"It's also really important for me to say that this is a matter of best practices with respect to the language—it is always worth doing a fact check, so I do not want to make it out like PolitiFact shouldn't exist because they're not always using the best communication technique. It's actually always best to fact check. That's the most important thing that can be done," Gibson says.

Research has shown time and again that any attempt to fact check or debunk misleading information is worth it. "So that's the most important thing, please fact check and debunk the information and spread that as far as possible," Gibson says.

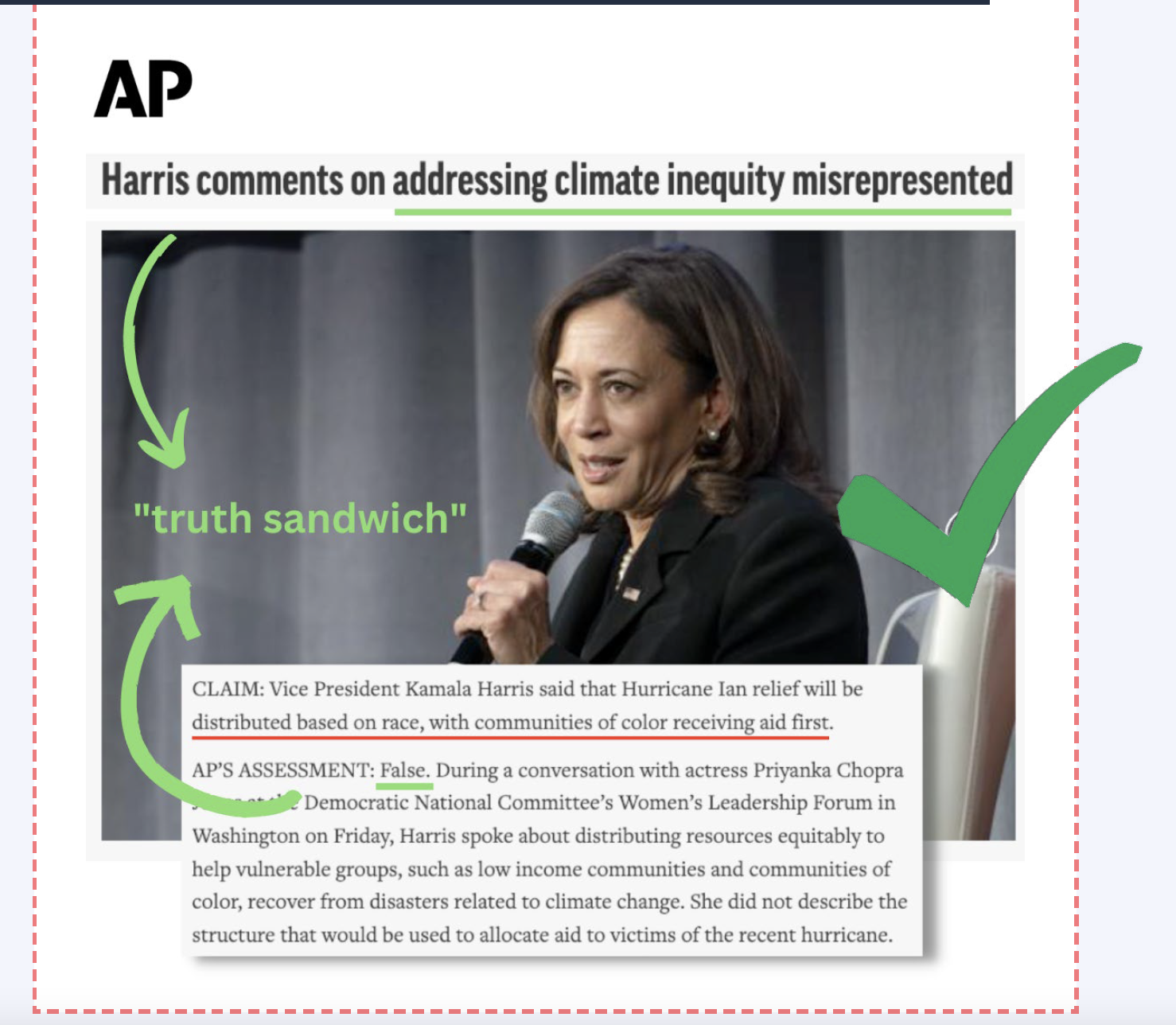

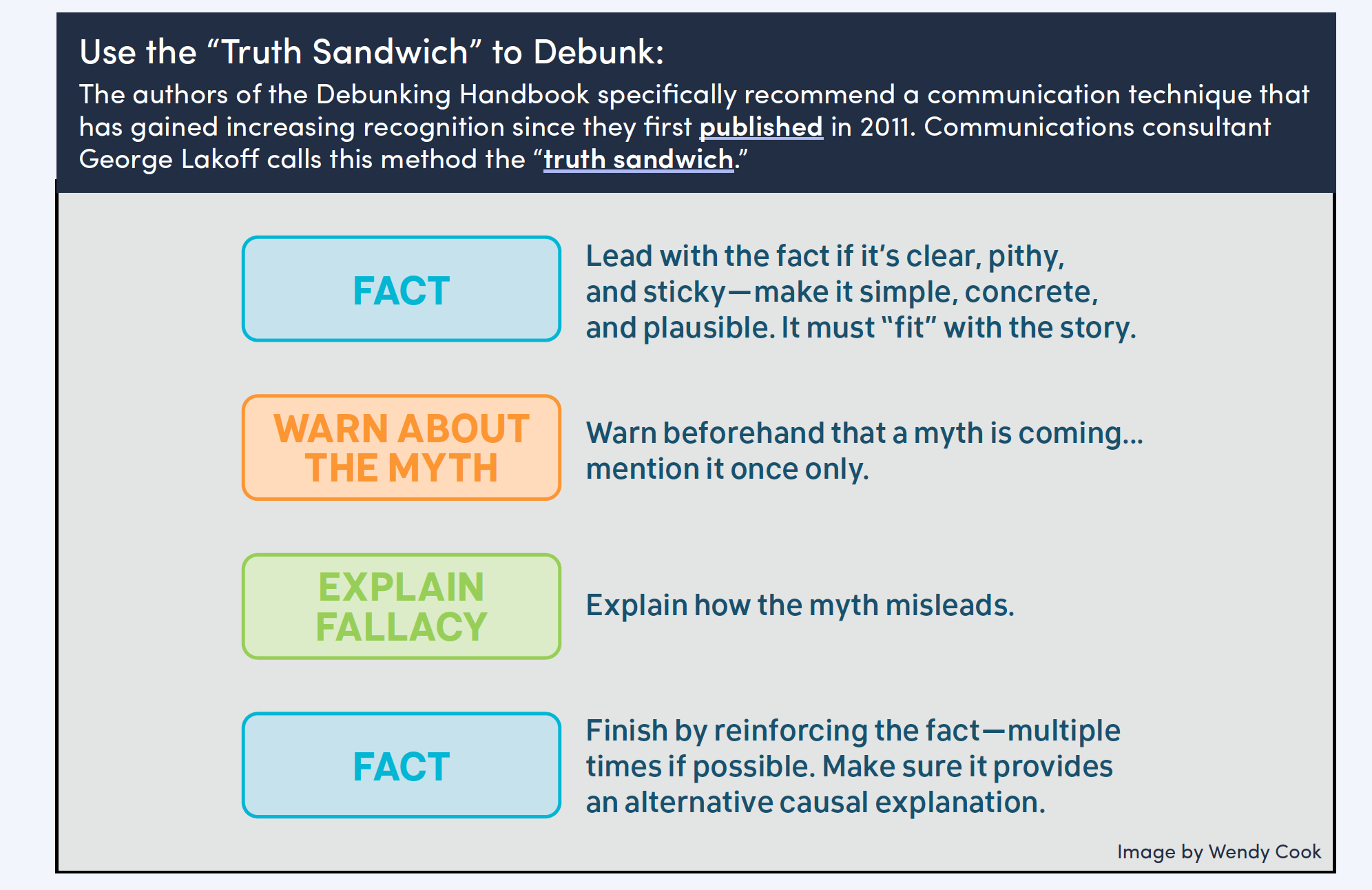

Embrace the Truth Sandwich

Rather than citing the myth in the headline, it's better to use the headline to introduce the fact that there is a myth out there, then debunk it, then remind people that it's a myth. It's an approach that's come to be called "the truth sandwich." The report uses the example below from the Associated Press as a good approach.

"First warn the audience that they are about to hear misinformation, and you give them important details on what the topic is, who said it and so on before you uplift any of the misleading information, and you explicitly warn them that they're about to hear something that's misleading after they've already heard the context in which it is false," Gibson explains.

He says it's something he first saw from academics like John Cook, who's at the George Mason University Center for Climate Communication, in publications like The Debunking Handbook, although George Lakoff (author of Don't Think of an Elephant!) may have coined the term. Both, Gibson says, "have been very clear that just because of how our brains work, it's really important not to mention the myth first," Gibson says. "It's important to mention the truth first and contextualize where the myth happened before you address it explicitly and then to follow up again by reiterating the truth. That's a much more effective way to dislodge misinformation from a human's brain after they've already been exposed to it."

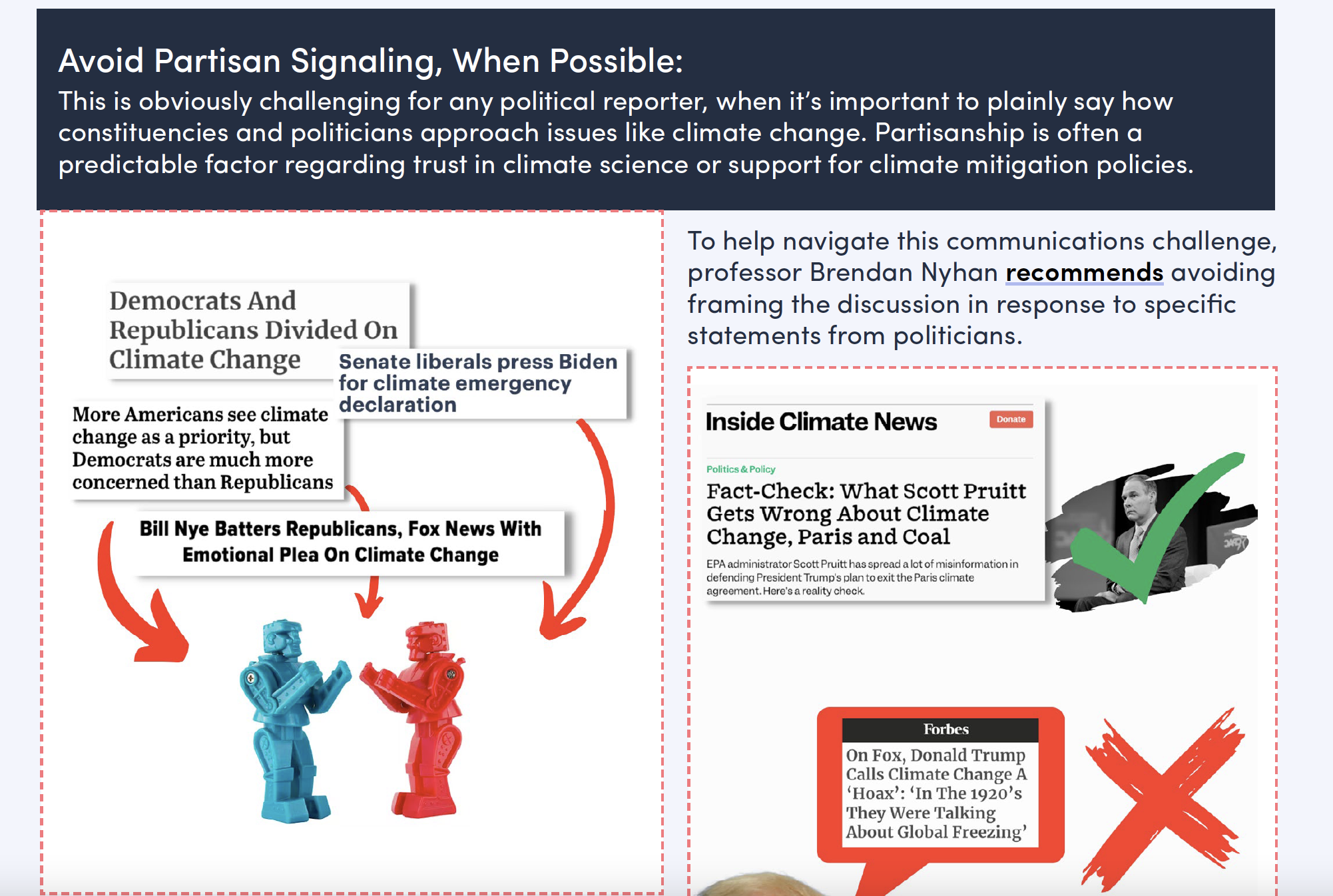

Avoid Partisan Signaling

This one can be tough in climate given the deeply partisan divide on the issue...but that's also why it's important to try to pull off. And here's where I do something that I also think is really important in the context of this conversation: admit that I have definitely made this mistake. I'm sure I've made others in the report too, but this one I know I've done recently. The point of folks like Gibson digging into the research on this and creating a hands-on guide is so that all of us can see where we're (unintentionally!) going wrong, try to do better, and have conversations about fixing the systemic things that perpetuat these problems too.

"This one's really tricky," Gibson says. "When I wrote publications for Greenpeace, which is an explicit activist organization, unapologetically, I tried very hard to never write 'conservative' or 'right wing ' in any of my posts. I did not want to signal to an audience that this is only something liberals should care about. But what makes it so tricky is the fact that when it comes to climate change, Republicans actually don't care and Democrats do care, and their constituents follow that exact pattern as well. And that is a factor in all of this."

So how is a reporter supposed to navigate this situation when partisanship is actually the factual reality of this situation?

"It does readers a disservice to signal that you should care about something or not as a result of partisan loyalty, and I think that it's something that can be navigated by framing the conversation around something else, and including statements from politicians later in the article, perhaps to help illustrate the partisan divide or the massive disparity in how science is accepted or interpreted depending on partisan affiliation," Gibson says.

Avoid the Passive Voice

Paging Flavia, brand editor-in-chief for Schlumberger, er, excuse me SLB! This one was totally new to me and is something I've been thinking about ever since speaking with Gibson last week. There are all sorts of grammatical reasons to avoid the passive voice but I had not thought about how it might preclude accountability.

"This was one of the most revelatory things," Gibson says. It came from a video (embedded below) published the Union of Concerned Scientists with communications expert Sabrina Joy Stevens

"When we just name disparities and outcomes without naming who and what is responsible for those disparities, we make it seem like a person's identity is responsible for the problem instead of the people and institutions discriminating against them on that basis," Stevens says in the video. She gives the example of sacrifice zones and environmental racism, which is frequently referenced like "Black and brown people are more likely to experience pollution," rather than, for example: "Oil companies are more likely to pick Black and brown neighborhoods to pollute."

So obvious and yet such a huge and necessary shift!

"I think I often fall into this trap just as much as reporters do," Gibson says, "where you're trying to do the responsible thing by mentioning that it's communities of color that are most disproportionately subject to polluting infrastructure, which is responsible for higher rates of chronic illness and preventable death. But that narrative doesn't include the fact that it's not an accident that those polluting refineries and facilities are built in communities that are lower income, majority people of color. Those are decisions that are made on purpose by executives, by politicians, by officials who have the power to permit them. And excluding that from the story does a disservice that is akin to victim blaming."

"Maybe something that can be done is in the final editing stage is to do a scan intentionally for points in an article where the passive voice is being used that actually leaves a lot left unsaid that precludes accountability," Gibson suggests.

It's a simple suggestion and one that seems like such an easy and obvious improvement. And yet, here too this guide highlights a major systemic problem in media: the shift away from accountability that's been underway since around the 1940s. In the Progressive era, and well into the 1930s, journalists' job was to hold the powerful accountable. But as the PR industry grew, and as industry in general began to spend more money and focus more energy on shaping public opinion and policy, that began to shift. Personally, I'd like to see newsrooms move very intentionally back in the direction of those early muckrakers and this whole passive voice-accountability issue highlights just one reason why.

The norms of media today very much steer clear of accountability. As a journalist, I am often asked to simply describe a situation. Attributing blame or responsibility is seen as bias or advocacy. "I think that's also, again, this thing where the way newsrooms operate, the need for brevity competes with the need for nuance and that can actually, unintentionally lead to more inaccurate reporting," Gibson notes. "And, you know, it's tricky because even best practices in this report might seem to contradict each other. Like I'm saying, some research indicates that it precludes accountability to write in the passive voice, but I'm also saying, please avoid partisan signaling! There's a lot of nuance here that's actually very, very hard to navigate if you're a journalist and I think that's why this is so important too. There's not a lot of time to sit and think about this if you're a journalist, you're on a deadline for story after story after story and you don't wanna get scooped. So I'm hoping that a report like this can help start conversations between journalists and editors and anybody else in the journalism profession about, you know, what are the next steps in terms best practices to navigate some of this stuff."

How to think about inoculation

The idea of inoculation against disinformation is one that I've talked to John Cook about myself and it strikes me as really important if we're ever going to get to a place where we're preventing, rather than reacting to, disinformation. But it's a complicated topic too, because when it works we don't see it, right? If no disinformation gets through, or if something is tried and falls flat, it's hard to really track that, whereas if a bit of disinformation goes viral we can look at where it began and how it spread fairly easily.

Gibson points to the false blaming of wind power for the Texas freeze disaster in February, 2021 as a very obvious example. "Most of Texas' city generation infrastructure that winter was thermal power, mostly gas and nuclear. That's the majority of what failed, and yet some politicians falsely blamed wind turbines for the collapse of the grid in 2021. So that's an example I think where inoculation could have gone a long way, but it's complex to anticipate. You can't anticipate a disaster like that necessarily, or when it's gonna happen, and that means there was no priority for journalists just to start writing articles to make sure people understand the composition of Texas's grid and things that could have inoculated against that misinformation."

The context we're in right now, in the leadup to COP27, however, is easy to anticipate. "There are certain predictable pieces of misinformation that will circulate, including against elitists and the irony of using jet fuel to go to a climate conference, those are arguments that out of context are very easy for people to scoff at and become cynical about," Gibson says. "And I think when there's a major event that is predictable, that's coming up, that is a good time for journalists to have a think about writing some inoculation pieces like predictable misinformation that will likely circulate in the next few weeks and why that is not true, the cherry picking that's required in order to make that sound reasonable in the minds of people who don't spend all day paying attention to these trends."

Again, innoculation is also complicated by the politics and economics of the newsroom. There's not necessarily a revenue incentive to write explanatory articles in advance of an event; stories that get out ahead of disinformation are nowhere near as clickbaity as those that come after the fact. "It's a much harder thing, I think, to get past the editor's desk than a story on a disinformation trend that just happened and had widespread impact," Gibson says.

You can listen to an audio version of this story in our podcast, wherever you listen to podcasts. If you appreciate our work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below!