Drilled Down: If More Climate Coverage = More Fossil Ads, Keep It

If you follow me on Twitter, you know I can be a bit ranty on there. It's where pre-coffee, bitchy morning Amy lives, what can I say? But some subjects really only merit rants and this is one of them: the increasing prevalence of fossil fuel ads on climate newsletters and other sorts of climate verticals.

Fossil fuel companies haven't advertised their actual products since around the late 1960s when PR genius Herb Schmertz at Mobil came up with what he called "affinity-of-purpose" marketing. Actually American Express got their slightly earlier with "cause marketing," a fact Schmertz admitted with good humor, regularly mocking his own less-catchy label. Of course it was all yet another rebrand for propaganda. Because what Schmertz was talking about, and creating for his company, were ads and campaigns that said nothing about oil or gas at all. Instead, they were advertorials that pushed the company's policy positions, or TV shows that just positioned Mobil next to highbrow content (Masterpiece Theater, yes, but also lots of other PBS shows). Today, all of the fossil fuel companies do this, whether it's Chevron pushing "renewable biogas" in the newly launched Semafor newsletter, or Schlumberger sharing a mealy-mouthed message about the world changing and the need for "sustainable energy" in the Protocol newsletter.

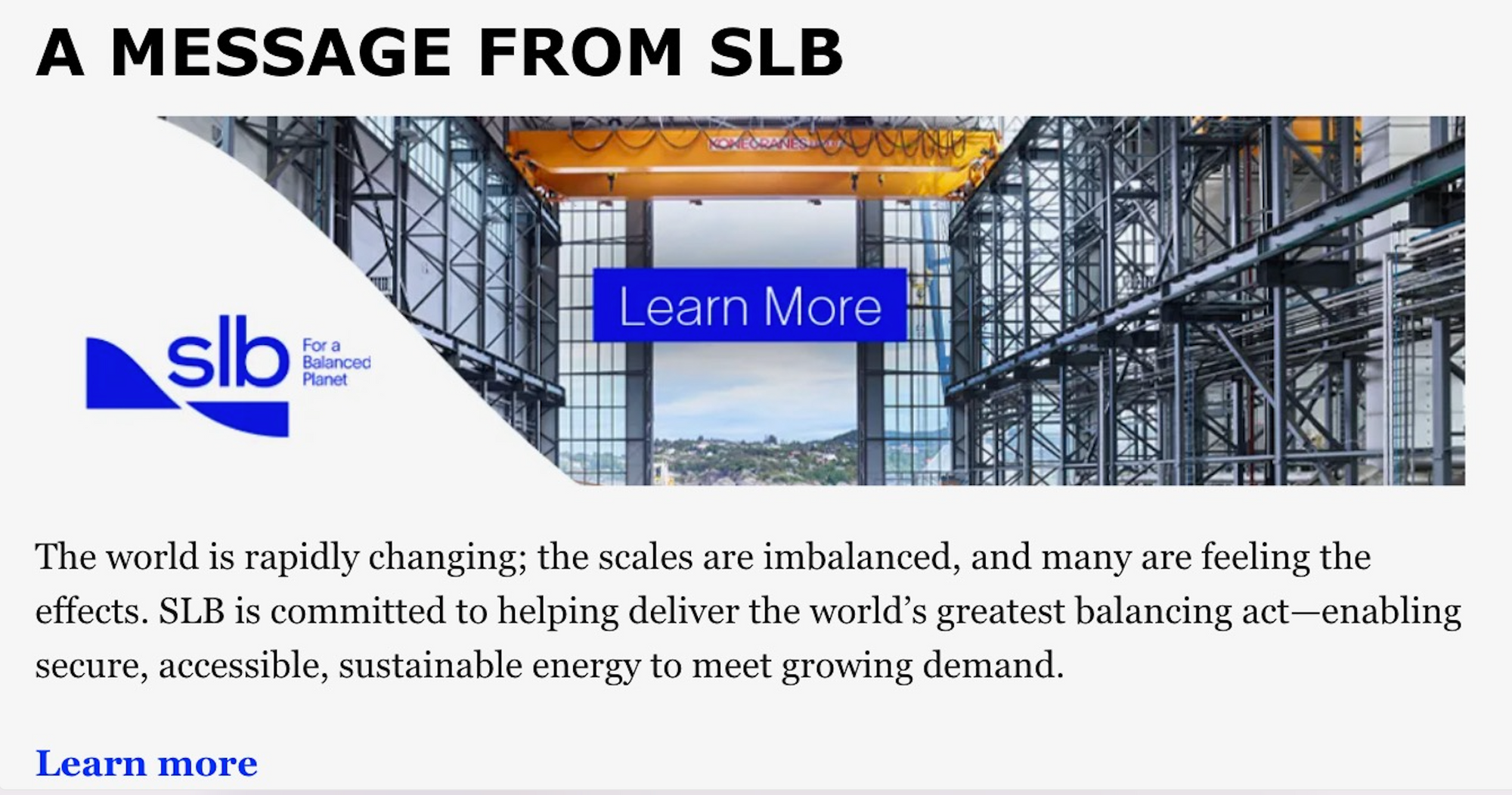

The Schlumberger campaign is a really good example of why it's all so problematic, and why there's suddenly so much of it.

First off, they've thrown off the name Schlumberger in favor of the completely unknown SLB. Hiding in the shadows for years as a favorite oil field services partner of ExxonMobil's, Schlumberger has become more visible recently. Extinction Rebellion Cambridge's Schlumberger Out campaign, for example, named them explicitly as a company Cambridge University shoudn't be taking research funding from. Just this week, activists blocked the Schlumberger building on Cambridge's campus with a giant Alice in Wonderland teapot. A spokesperson for the group, Violet, said the intention was "to highlight the absurdity of the situation. This building is specifically designed to research and develop new drilling techniques, yet the International Energy Agency says there can be no new oil and gas fields if we are to keep to 1.5˚C of warming, something the University of Cambridge has committed to."

Good time to become SLB! The change happened yesterday—at the same time as the protest. Schlumberger even changed its name on LinkedIn, that's how you know it's serious! They are now a "global technology company, driving energy innovation for a balanced project." Wow, who are the ad whizzes who came up with that one? Well, we know actually, because LinkedIn. And also because the geniuses over at Clean Creatives will answer questions like "When did Schlumberger become SLB, and who did that brand work?" in a matter of minutes.

Flavia Barbat, brand editor-in-chief for Schlumberger and editor-in-chief at Branding magazine, published a celebratory post yesterday, noting: "While it's easy to criticize and troll, it's hard to take responsibility for your actions and the education of others."

Okay, let's take a look at what "taking responsibility for your actions" translates to for a multinational oilfield services company.

That's a whole lotta passive voice in service of taking responsibility, Flavia! The world is just changing, all on its own, the scales are imablanced, "many are feeling the effects." Indeed!

In the comments, she gives kudos to the Brandpie team for doing a "fantastic job." Brandpie calls itself an "an independent consultancy specializing in purpose-driven transformation." Purposes, like...increasing profits for the fossil fuel industry?

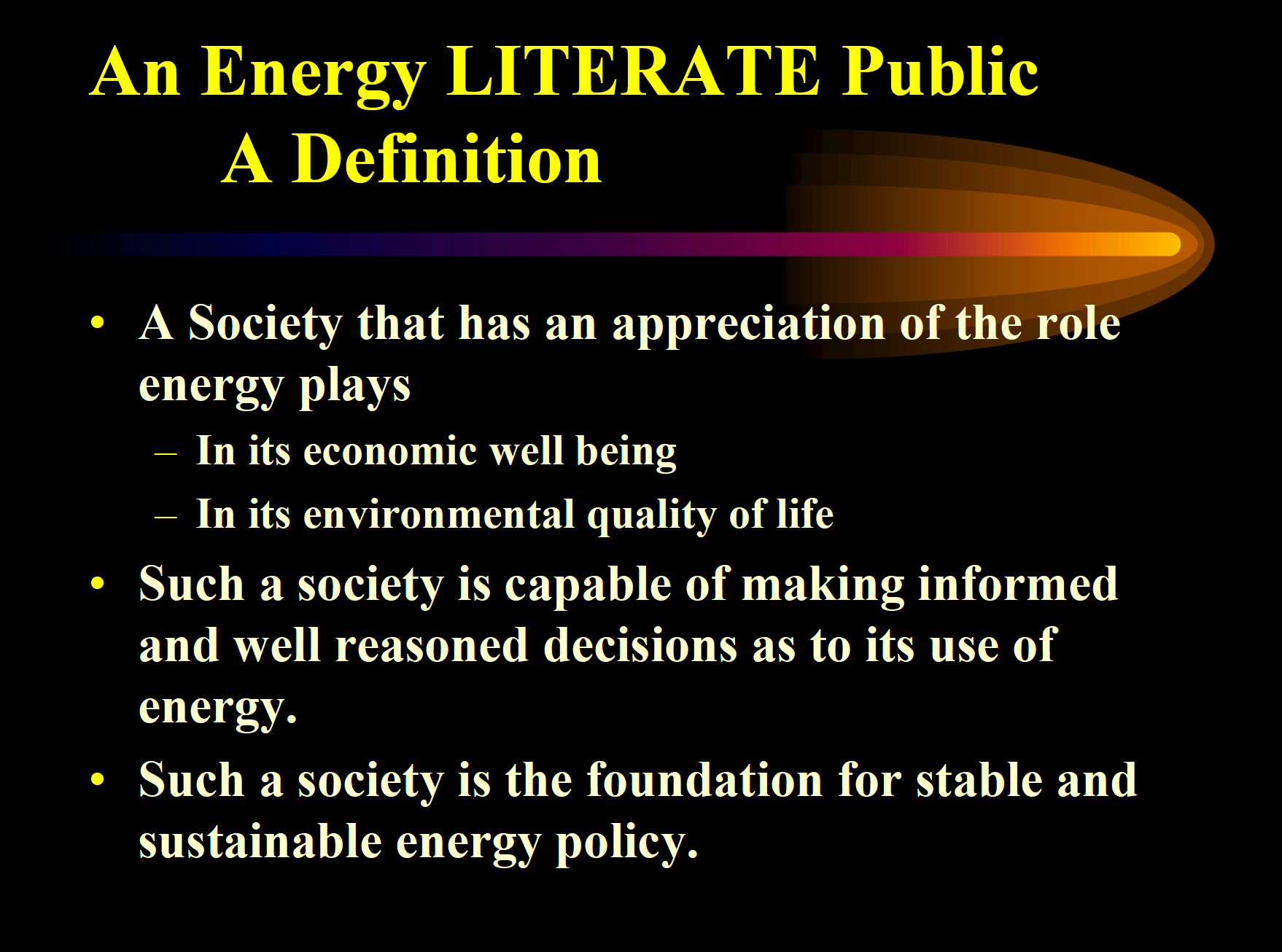

According to Flavia, "SLB" (I believe it's pronounced "schlub") is "investing in ensuring that the wider population beyond their industry's walls have access to the right information when it comes to energy demand and a truly sustainable way of meeting it."

If that sounds like it came right out of a 1990s industry presentation on the importance of educating the public about a balanced approach to energy, well...

All jokes aside...who is Schlumberger to decide what the "right information" is on energy, climate, and that old canard "sustainability"? And why on earth would any outlet that's decided to invest in climate coverage platform that drivel?

We covered the fossil-free research movement last week. In the course of reporting that story, I asked Connor Chung, with Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, what he thought about a common response to the call for universities to stop taking research funding from fossil fuel companies: it's not like there's a giant pot of money waiting in the wings to replace fossil fuel funding, what if saying no to oil companies means less climate research overall?

"We'r okay with that," he said. "I think it's better to have less research than to have compromised research."

Josh Penrose, one of the organizers of Schlumberger Out at Cambridge, had a similar take. "I think they should not have a seat at the table because they're a company whose business model is diametrically opposed to the science-based climate action that we need at the moment," he said. "And it's just wrong to endow them with the power to influence such a transition."

I'm starting to feel the same way about media. Does it really benefit anyone if we have more climate sections on websites and in newspapers, and more climate newsletters, and more climate podcasts, if they're all sponsored by the industry? Wrapped in propaganda about changing world and the need for a balanced-energy approach, or outright lies about the potential of carbon capture or algae biofuels or biogas? I think it might actually do more good if there were fewer platforms for fossil proganada, even if it meant slightly less climate coverage.