Planet of the Ecofascists

Did I want to spend two precious hours of work time watching a badly produced film narrated in monotone? No, no I did not. But as the online debate over Planet of the Humans droned on, culminating in an environmental filmmaker announcing triumphantly that the film’s distributor would be taking it down, followed by a lifelong climate denier urging everyone to go watch this “takedown of the corrupt Big Climate mob,” I realized okay, activists are too mad, denialists are too angry, I’m gonna have to actually watch this thing.

The unfortunate thing is that there are kernels of an important and interesting film here. It’s true that the renewable energy supply chain is worrisome (check out Maddie Stone’s excellent reporting here and here on lithium mining, for example). Large environmental groups do often get too cozy with corporations, and the climate movement includes plenty of people who are a little too into fame and fortune for my taste, too. The idea that “solving” climate change is simply a matter of new technology or energy sources, that no social or economic shifts are required at all, is problematic and it’s an idea that is still sometimes championed by technocrats and some high-profile climate scientists and activists. It’s also true that biomass, once heralded as a “green” energy solution, has turned into a global climate boondoggle of epic proportions.

But it’s also an idea that’s been mostly abandoned by the environmental movement, which seems to be Moore’s and director Jeff Gibbs’ primary target here. Moreover, the only “solution” proposed by the filmmakers—population control—is just the other end of the same spectrum of lazy thinking. On the one side you have technocrats saying there’s no way to change social norms or human behavior and our only hope is technology that enables the status quo, on the other you have ecofascists saying there’s no way to change social norms or human behavior and our only hope is fewer humans … again, to enable the status quo.

Laziness drifted into the nuts and bolts of this film as well, and I’m not just talking about the technical glitches, of which there are many. Good documentary filmmaking hews closely to the ethics of journalism. Sure you’re looking for a narrative thread or framing to keep people engaged, but you don’t go out looking for people and data points that prove your argument. Doing so veers sharply away from documentary, which Planet of the Humans purports to be, and into commentary. On this front, the key issues are the film’s tendency to lean on wildly outdated information (a big faux pas when you’re dealing with technology and ideas that are rapidly evolving), cherry-picked and often inaccurate data points, and a bizarre obsession with Big Green as the real problem blocking action on climate. Let’s explore these issues in detail:

- Old data and information If you’re going to make a film that spends more than an hour tackling the pros and cons of renewable energy, your information needs to have been updated in the last five years. This is an industry and a set of technologies that are evolving rapidly, and as far as I can tell, the most recent information Gibbs has is from 2012. He starts off his rant about both electrical cars and solar at a Chevy Volt event in 2008. I kept waiting for him to move into the present from there but it never quite happened. Again, there’s a missed opportunity here: why not call out GM for greenwashing? Or update your reporting on electric cars and note how many cars are still plugged into fossil fuels? Failing to do so, or to provide current, accurate data on renewables undermines any larger point the filmmakers were aiming for.

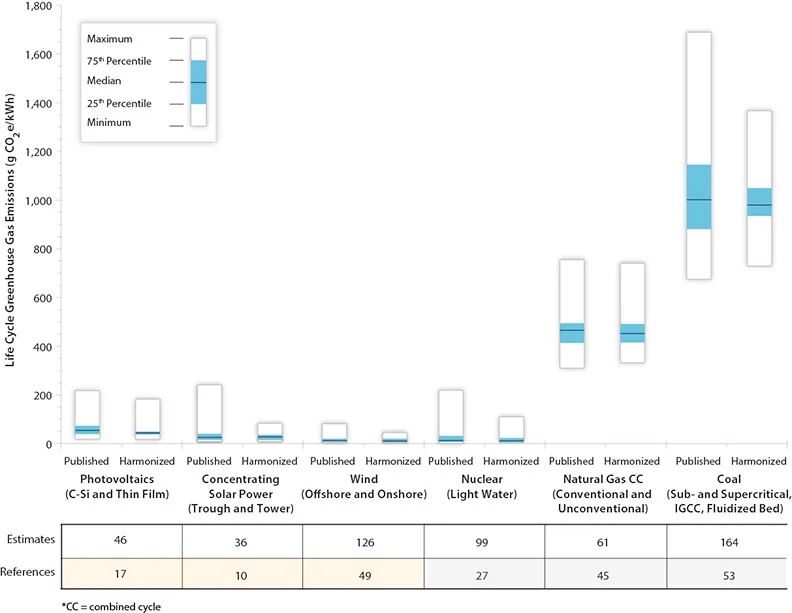

- Cherry-picking and Inaccuracies. Most of the inaccuracies in the film are related to the issue of using outdated information, but some are the result of cherry-picking, while others seem to indicate a general lack of understanding. Key issues Gibbs points out over and over again are the inefficiencies and intermittency of renewables, the fossil fuels associated with both constructing and operating renewables at scale, and the short lifespan of some turbines and solar panels. As Zeke Hausfather pointed out, the lifecycle impacts of wind or solar are tiny compared to those of coal or gas.

Which is not to say that efforts shouldn’t be made to reduce those impacts, but that’s not the argument Gibbs makes. His takeaway is that renewables are just as bad as fossil fuels and therefore ought to be abandoned entirely. Or as producer Ozzie Zehner puts it, “One of the most dangerous things right now is the illusion that alternative technologies like solar and wind are somehow different from fossil fuels. You use more fossil fuels to do this than you’re getting benefit from it. You would have been better off just burning fossil fuels in the first place, instead of playing pretend.”

Gibbs also notes that solar panels are only 8% efficient—meaning only 8% of the sunlight that hits them can be converted into energy. That was true 12 or 13 years ago when Gibbs was gathering footage, but these days the average is at least double that, with the most efficient panels delivering triple that. Advances have been made in both energy storage and forecasting to address the intermittency problem as well; and as Ketan Joshi points out, Gibbs creates a circular argument here: if utilities have battery storage to help smooth out renewable energy supply and demand, it’s filmed with sad music while Gibbs bemoans the materials required to create that battery, if they don’t then the lack of storage is the problem.

Is there room for improvement in renewable energy technology and storage? Absolutely. Does that mean they’re as bad as fossil fuels and a project that should be scrapped altogether? No.

The ol’ population argument. I've been covering climate change long enough that the population debate has come and gone twice in my career, and I read enough history to know it came and went at least two or three times before I started too. But Gibbs thinks he's had a real breakthrough here: There are just too many humans consuming too many resources. Solution? Not reduced consumption, but fewer humans. Note that every expert making this argument in the movie is white and upperclass and from the West. Population growth is low in developed countries, so the argument for curtailing population is generally targeted at developing countries, which also happen to be low-income black and brown people. These countries also happen to be the world's lowest emitters, so the equating of population reduction to emissions reductions starts to really fall apart here. The last time I covered this issue, around 6 years ago now (so around the time Gibbs had wrapped up reporting for this film), I remember being struck by how casually white academics at elite universities would make the argument for reducing population, specifically in developing countries. When I asked a Stanford University professor how she squared her own reproductive choices with the call she was making for global population reduction, she replied, "I mean my children are much more likely to solve big global problems like climate change, statistically, so I really don't see it as an issue." Placing a higher value on some humans than others and trying to skew the birth rate in favor of those more valuable humans is called eugenics and it's disgusting... and not a solution to climate change.

An obsession with Big Green and no discussion at all of Big Fossil. For some reason, the only time we hear any modulation in Gibbs’ tone at all is when he’s critiquing environmental groups, particularly 350.org and The Sierra Club. Honestly, if you’re gonna critique the Sierra Club and you’re making a movie using outdated arguments, you’d be far better off taking aim at Karl Pope taking $25 million to push the natural gas bridge fuel narrative than attacking Mike Brune and Mary Anne Hitt for taking Bloomberg’s money to shut down coal plants. Have some coal plants been replaced by natural gas? Yes, unfortunately. Is that something the Sierra Club has recommended or supported at any point in the Beyond Coal campaign? Not in any way.

With Bill McKibben and 350, Gibbs again trots out old and outdated information, including footage of McKibben praising biomass more than a decade ago (he has resolutely opposed it since 2016). Gibbs also attempts to “gotcha” McKibben with footage in which he stammers about where the organization’s funding comes from, and then admits to receiving some funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. Aha! Except for the fact that while the Rockefellers money undoubtedly comes from oil, the foundation has spent more money, more aggressively to attack climate change and hold oil companies accountable than any other nonprofit. Are there issues with philanthropic funding? Of course. There’s no clean money out there, it’s all attached to fossil fuels or slavery one way or another. But to insinuate that McKibben, who has never taken so much as a salary for his work with 350, is somehow in it for the money is disingenuous at best. It’s also given more fodder to climate denialists, which seems wholly unhelpful and unproductive in the current moment.

Moreover, in leaving out fossil fuel companies, utilities, and automotive companies from his narrative, Gibbs ignores the primary reason that renewables still have a ways to go before delivering on their promise: a decades-long campaign intended to stop both regulation and the development of competitive renewable energy technology. Had the scientists working to develop lithium batteries, solar, wind and nuclear technologies back in the 1970s and 80s—many of them employed by oil companies—been allowed to continue their work, we’d likely be much further along not only in the technical capacity of these technologies, but also in the sourcing and waste-management side of things.

One last thing: Although I think Planet of the Humans is a steaming pile of misleading garbage, and that the filmmakers ought to issue retractions and corrections just like any media outlet would be required to do, I don’t necessarily think anyone is served by calls to remove the film from circulation entirely. In my opinion, that feeds into the denialist machine more than anything else; they’re already crying censorship and using the call for the film’s removal as a marketing tool, calling the film “the documentary environmentalists don’t want you to see.” To my mind, that only gives its bogus arguments more power.