Podcast: Secret Tribunals and Hand-Picked Arbiters—A Little-known System Undermines Environmental Regulation

When national governments legislate environmental protections through laws like the Clean Water and Clean Air acts, and agencies like the U.S. EPA set nationwide pollution rules based on those laws, you’d think those rules would apply to every firm that does business inside that nation’s borders.

But on a host of issues, from water quality to greenhouse gas pollution, managing mining waste, and more, there is a little-known clause included in most investment treaties and trade agreements that can upend national environmental and climate regulations. It’s called “international investment arbitration,” and in certain situations it binds countries attempting to enforce national environmental regulations on industrial development and facilities, including fossil fuel extraction, to a shadowy dispute-resolution process.

That process is a big part of the Chevron-Ecuador case that we’re investigating in season five of the Drilled podcast and a series of related articles this month in Drilled News.

In broad strokes, the international investment arbitration system gives companies a certain amount of legal cover that — they claim — they need in order to confidently invest in projects in developing countries. When a so-called “investor-state dispute” arises, such as when a company wants to take a government to task for what it considers overly burdensome environmental enforcement, the firm can file formal complaints with international tribunals. The tribunals in turn create an “arbitral panel,” generally consisting of three international law experts (although not judges), which hears legal arguments from both sides. Then the panel decides whether the state in question has breached either a trade agreement or its own laws and, if so, what it owes in financial damages to the firm.

While in some cases proceedings and relevant documents are made public, in others they are kept secret, including the Chevron-Ecuador case.

In recent decades, firms have routinely turned to international investment arbitration to punish countries for attempting to enforce strong environmental protections. In one case, which I have reported for The Guardian, El Salvador banned mining in 2008,following a mining disaster that contaminated much of the country’s drinking water, then denied the international firm Pacific Rim an exception that would allow it to keep mining., So the firm filed an international arbitration claim, effectively suing El Salvador for having the nerve to try and protect water quality.

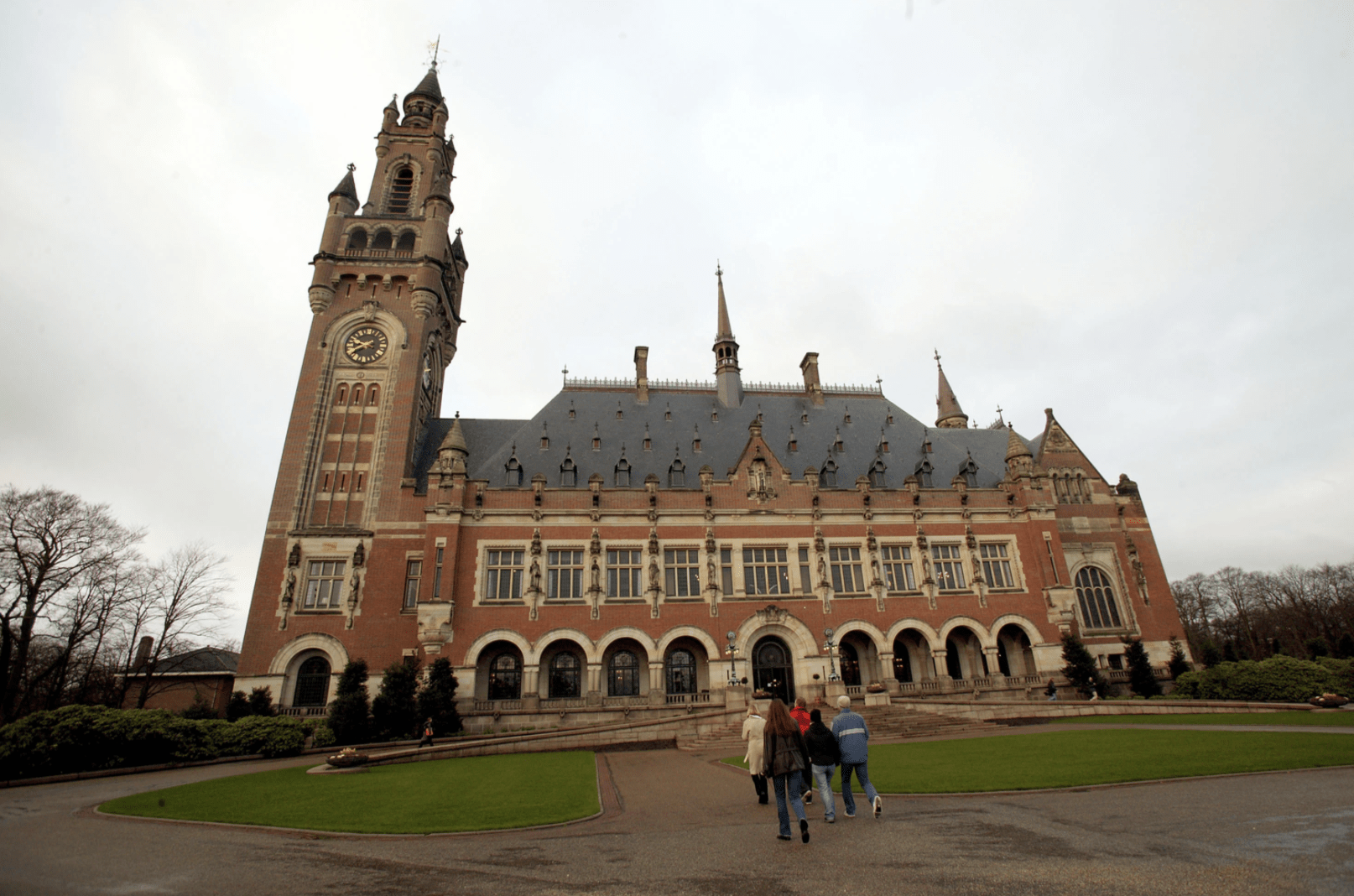

In the Chevron-Ecuador case, in 2009 Chevron filed a claim before the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague, alleging that Ecuador had violated a U.S.-Ecuador bilateral investment treaty simply by allowing the case to be heard in its courts. The firm filed that claim six years after the trial started and two years before the court handed down a verdict but ordering Chevron to pay $8 billion in compensation for the environmental harms and human suffering caused by its toxic waste dumps in the Amazon.

A new report from the International Institute for Environment and Development highlights how these mandatory arbitration clauses could to make it that much harder for countries worldwide to take strong climate action: Since most of the world’s coal plants and oil-and-gas drilling sites are governed by international trade treaties, and those treaties almost invariably include arbitration agreements, fossil fuel companies have a great deal of power to file complaints against countries whose cuts or caps on carbon pollution interfere with their profits.

Because so much of what goes in these arbitration proceedings is kept secret, even the relatively few Americans who know that this system exists may not fully grasp how much potential it has to upend national environmental and climate regulations. So we called up Marcos Orellana, an expert in international human rights law and the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, for a crash course.

Listen to the podcast episode here.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Amy Westervelt: I’d love to have you start with a general explanation: what is international arbitration and how is it used by American companies?

Marcos Orellana: At its core, international investment arbitration is a system that allows corporations to sue states for damages, before panels of arbitrators. These days, most arbitration cases are brought under international treaties on investment protection. These instruments typically grant corporations the right to claim compensation in cases where the government takes a measure that breaches the standards of protection in the treaty and that results in economic loss for the investor. Arbitral tribunals are typically composed of three panelists. One of the panelists is appointed by the corporation, the claimant. In theory, as the World Bank and capital exporting countries often argue, international investment arbitration helps foster economic development in developing countries, and it does so by building confidence in foreign investors.

That’s the theory. In practice, however, the corporations are using the arbitration system to discipline governments for their own interests. And this is often done at the expense of the public interest. How does this work or how does this happen? Well, in the arbitrations, corporations often argue that their expectations for profit have been frustrated, that they have been frustrated by the government that adopts a law or a decision or a regulation. And they, the corporations, demand to be compensated for the profits they expected to make. Since arbitral awards can run up to tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, and since even the legal fees involved—the counsel and the costs of the arbitration—can run into the millions of dollars, this puts a lot of pressure on government officials.

Let’s recall that many of the respondent states in these cases, they have limited budgets. They might be small developing countries that are facing a set of priorities, competing priorities, and they have to struggle to satisfy health and education and times, food and water and environmental protection. And so we’re talking about tens of millions of dollars of costs that can really put a dent into the budget of a state. So those are the basic contours.

The international investment arbitration system can be described as a private system of adjudication that decides on the propriety of governmental measures, but it lacks the safeguards for accountability and transparency that characterized constitutional democracies governed by the rule of law.

Arbitration came to replace colonial systems, colonial systems of extraction of domination.

When the former colonies acquired independence in the advent of decolonization, largely after the Second World War and the advent of the United Nations, the former imperial powers needed a legal system to protect the economic interests of their corporations, and international investment arbitration offered such an alternative. Today, in this current day of age, many in civil society see the arbitration regime as yet another tool of corporate globalization. This is because when governments regulate in the public interest, they become the targets of corporations that utilize the arbitration system to challenge those acts of authority.

I would comment that this is particularly problematic in the age of climate change because governments must reduce the emissions of greenhouse gases to face the climate emergency, the existential risks that flow from climate change, and of course, this change in direction affects the expectations and the interests of the oil and gas industry. One last thing that I’d comment on is the tension that in practice arises between international investment arbitration and international human rights. And this is because international law has come to recognize how a clean and healthy environment is indispensable for the enjoyment of human rights. The investment arbitration system, however, puts an obstacle to the abilities of governments to take measures to transition towards sustainable development and to secure respect and protection of the fundamental right to live in a healthy environment.

Thanks Marcos. I’d love to have you give an example of how a company might use this to, for example, challenge a government over an environmental law that they don’t like.

Yes, there are many examples of states passing environmental laws and then being taken to court by corporations that are dissatisfied by those laws. One example comes to mind, concerning hazardous waste in Mexico, the so-called TecMed case. It’s a few years old now, but I think it exemplifies the issues that arise in these arbitrations. In that case, a hazardous waste confinement was located in downtown Hermosillo in Mexico, and the government was concerned and the people around the confinement were concerned that the trucks going day and night in and out of the confinement with these hazardous wastes were posing a risk to to the environment and to the health of the population. The company in question began to enlarge the confinement without having the necessary permits. And as a result, it was fined. There were proceedings by the administrative agencies in Mexico. And the government began to study the possibility of moving this confinement outside of the downtown area. Laws were passed that required that hazardous waste confinement be located far away from urban centers.

However, the negotiations with the company did not progress very far. Eventually, the government decided that it would not renew the concession for the operation of the hazardous waste confinement. And at that time, the company took the government to the arbitral system. And that’s when the arbitrators replace the role of domestic courts and begin to apply loosely defined treaty standards. They eventually considered that the corporation had an expectation to make a profit out of its investment, but that profit had been frustrated by the measures that had been taken by the government to protect the people around the confinement. I should also comment that in that specific case, the community mobilized. They began to protest against the illegal expansion and so forth. And so the government was also giving expression to the concerns and the interests of the people that were mobilizing. The tribunal, however, considered that those protests could not be foreseen and that they were they did not have a scientific basis. There was no evidence that hazardous waste had indeed compromised the health of the population. And in so doing, then they declared that Mexico was liable to pay the company millions of dollars for the measures it had taken.

So this, again, goes to show how in a domestic court, the balancing of the public health, the environmental issues, the human rights issues would have received a different light than the uni-directional character of the arbitration that focuses on the corporation and whether the government’s measure has frustrated its expectations of profit.

OK. So, I know that you are not involved in this Chevron-Ecuador case, but as someone who knows the system well and has seen lots of different types of cases, I’m curious about whether it popped up on your radar and what your thoughts are.

Yes.I have not been involved in this case, but have managed to observe it over the years. It’s hard to miss, given its prominence in the field. The one thing that I would observe is that this is a massive case. It’s a massive case. The arbitration itself spans thousands of pages, numerous awards and procedural decisions. Prior to the arbitration, there had been litigation in federal court in New York for nine years. There was also litigation in Lago Agrio in Ecuador and trial litigation, appellate court litigation, Supreme Court litigation in Ecuador. The Ecuadorian constitutional court was also seized. There has been litigation in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, the Netherlands. The International Criminal Court received a letter as well. And there’s still ongoing litigation by Chevron against the plaintiff’s counsel in the United States.

And it goes to show how difficult it is to hold a big oil company accountable for environmental harm. Chevron has spent hundreds of millions of dollars in legal fees. Those monies could have been used to prevent environmental harm or to clean up the pollution. How does it compare to other cases? Well, one thing I would note is the arbitral system is opaque, it is known for its lack of transparency. This is a big problem because the arbitrations involve the public interest. They involve the scrutiny of public law measures. And so they should be heard under the safeguards of transparency and accountability that characterize due process and the rule of law.

But these arbitrations often are conducted behind closed doors without the public having access to the proceedings. In some cases, high profile cases involving environmental protection measures, the arbitrations have opened up and they have allowed for public hearings and they have allowed for the public to present so-called amicus curiae briefs. This is a Latin term for a written brief that presents a perspective that may not have been developed by the disputing parties and that is helpful for the tribunal to receive. In this case, however, in the end, the Chevron Ecuador case hearings were held behind closed doors. Civil society was not allowed to intervene as amici. And from that angle, the outcome in favor of Chevron is not surprising. But all that said, however, the outcome is surprising in some aspects. And one of the aspects that I think has to some degree startled a number of observers is the far-reaching character of the awards. And this is because the arbitration system is often sold to policy makers and to the public as one of simple compensation for loss. The bottom line is, it is argued, is that if a foreign investor suffers economic harm because of something that the government did, then it should be compensated. And the example, the caricature even that’s often presented is a corporation owns a mine that is expropriated by a military junta that gives the property to the nephew of a general in power. Then, of course, the company should receive compensation.

But that’s not what’s going on. That’s not what went on in this case and not generally what’s going on in the field. In this case, the panel, the arbitral panel crafted a range of remedies that go well beyond the issue of compensation for loss. It directed Ecuador to preclude enforcement of the judgment of its national courts. So preclude enforcement. That shows how deep this system penetrates the sovereignty of the state. The panel also declared that Ecuador would be liable to Chevron for any recovery. So in other words, if the Lago Agrio plaintiffs are able to enforce the judgment rendered by the Ecuadorian courts in some jurisdiction around the world where they can find Chevron’s assets, Ecuador would be liable to Chevron for any recovery that the plaintiffs make.

Wow.

Yeah, it’s quite far-reaching. It is not just an award that says, as is typical, that the state has adopted a Measure X, this measure has cost Y harm and the tribunal orders the state to pay 50 million dollars to the company. That’s not what’s what’s happening here. One of the things that this shows is that international investment arbitration is not just about money.

It is foremost about governance. Who takes decisions and for whom? Who benefits from those decisions? So in that sense, it is the system that removes the scrutiny of governmental measures from courts of law and places it in the hands of three arbitrators. In this specific case, one of the arbitrators often sits in arbitral panels because he is appointed by corporations. Let’s recall that typically there are three arbitrators and the corporation, the foreign investor gets to appoint one of the arbitrators. So in that sense, it was no surprise that this person would favor Chevron’s interests. The other two arbitrators were English. One, a commercial lawyer who recently passed away. So may he rest in peace. And the other is an international law professor. So I think it’s fair that we can ask, ‘Can we expect two English white males sitting thousands of miles away from the lands polluted by Texaco to appreciate the significance for the indigenous peoples that lived in those territories of the environmental destruction that Texaco caused in the 1970s in Ecuador?’ I think that their decision shows that they did not. That the arbitrators simply focused on Chevron and its narrative in disregard of the environmental and human rights calamity caused by Texaco. And to be fair, Texaco and PetroEcuador. I think that the disregard for this calamity shows the uni-directional character of the investment arbitration regime, a regime that focuses on the corporation’s interests and its narrative and does not regard the environment and human rights. Perhaps I could elaborate on an example to illustrate this point.

That would be great. And then I do want to have you talk about how this undermines the Ecuadorian constitution and the right to a healthy environment and in general how it undermines countries’ sovereignty on those points.

That is exactly one of the issues that the arbitral tribunal addressed. Now in in a democracy, a constitutional question would be addressed by a constitutional court. But in this instance, there was an issue concerning a contract between Texaco and the Ministry of Mines and representation of the government that raised this issue in the arbitration. So perhaps to step back, I think this is a good example: in one of their awards, the arbitrators set out to interpret the right to a healthy environment in Ecuador’s constitution. Chevron argued that it had been released from liability for collective claims under the right to a healthy environment by virtue of a release contract that had been concluded between Ecuador and Texaco in 1995. If we recall this contract under that, under its terms, Texaco would carry out some remediation work in exchange of release for liability from the state and PetroEcuador. But the scope of work in this contract was limited. This left source areas of contamination unremedied. There is evidence that indicates serious shortcomings in the remediation efforts that were actually carried out. Despite all this, in 1998, Ecuador approved Texaco’s works and released it from liability related to contamination from the oil operations. So this is the contract and the release that Ecuador that Chevron argued was at issue in this case and precluded the exercise of jurisdiction by Ecuadorian courts of claims concerning the collective dimensions of the right to a healthy environment.

And so it asked the arbitral tribunal to declare so and declare that Ecuador, by allowing its courts to exercise jurisdiction, was violating the contract and the bilateral investment treaty between the United States and Ecuador. The tribunal approached this and despite the fact that pollution was not cleaned up, that environmental problems were not resolved, the tribunal concluded that the contract between Ecuador and Texaco meant that Chevron could not be sued on the basis of the collective dimensions of the right to a healthy environment in the Ecuadorian constitution. The tribunal considered that the government could dispose and did in fact dispose of this constitutional right by a contract. Now, I would comment that the tribunal’s decision is not compatible, it doesn’t comport with international human rights law or with constitutional law, for that matter. This is largely a commercial frame looking at contract law to approach what are public law issues of constitutional human rights theory.

A state cannot contract human rights away. Human rights are inalienable. They belong to humans. They belong to the people.

The state cannot abrogate human rights. Least of all by contract. The notion that a country and a corporation can in a contract deprive the people of the state from a basic human right can only be understood by reference to the arbitration as a system for advancing corporate interests at the expense of the rights of peoples.

One could comment that it was expedient, perhaps, for the tribunal to interpret the right to a healthy environment in Ecuador’s constitution in a manner that shielded Chevron from liability. That released it from any claims. Otherwise, the tribunal may have had to look at the environmental realities in Ecuador. The lack of remediation, the ongoing contamination, the fact that dirt was moved from pits, that certain pits that had been covered up are still leaking. That communities, many communities are still without adequate food, without adequate water and so forth. That is something that Chevron has worked very hard to avoid in this case.

And I would say that Chevron has largely succeeded. It has largely succeeded in making this case story about the plaintiffs lawyers, about Steven Donziger. But I think it’s important not to forget what this case is really about. If we recall, the indigenous peoples in the Amazon, the Huarani, the Cofan, and other indigenous peoples, they lived in a pristine rainforest environment prior to the arrival of Texaco and the oil boom in Ecuador in the 1960s and early 1970s.

The extraction of oil by Texaco and Petroecuador was without regard to the protection of the environment. It was without regard to the rights of affected indigenous peoples first operated by Texaco, as I mentioned, and then taken over by Petroecuador, oil operations severely impacted indigenous peoples traditional lands. The the oil boom in Ecuador has imposed loss of life, health, territory and culture. Indigenous peoples have not received reparation for the violation of their rights. The arbitral tribunal concluded this was beyond their mandate and therefore it was not their problem.

It is not surprising. This is not surprising, as international investment arbitration focuses on whether the government has wronged a corporation, but not on the environmental damage that may have been caused by that corporation. This imbalance is creating deficiencies in the international legal system. And this award is an example of that.

Can you explain what happens when there are court proceedings happening in parallel with arbitral proceedings?

Traditionally in international law, before a claim can be presented by a non-state actor, to an international tribunal, there needs to be exhaustion of domestic remedies. This is a term of art that means that a person or a corporation that feels that it has been wronged in order to present a claim first must go to national courts and give the state the opportunity to resolve problems before being confronted with an international claim in investment arbitration. However, there is no requirement, at least not explicitly or typically. There are so many bilateral investment treaties, thousands of them. But typically they don’t establish an exhaustion of domestic remedies requirement. What many of these treaties do establish is a choice whereby the investor must choose whether to go the route of national courts or go the route of an investment arbitration. And investors usually elect investment arbitration because there, they get to appoint one of the typically three arbitrators and they get to choose which arbitral rules will govern the arbitration, which is also relevant for the conduct of proceedings and the enforcement of any awards.

So that’s a particularity in the field where corporations are able to do some forum shopping to advance claims in whichever forum and in whichever way suits their interests best. So when corporations are well-endowed with resources and have the ability to hire scores of lawyers, they can really drown plaintiffs in litigation that is expensive and in various forums.

A few years ago, a company that had its headquarters in San Francisco, Bechtel, it acquired a water concession in one of the poorest countries in the world, in Latin America, Bolivia, in the city of Cochabamba. And soon after taking over the water concession, it raised prices exponentially. It even began collecting water fees from water taken from wells that had been constructed by communities. So it was expected that Bechtel would invest capital to increase coverage and secure access to water, but instead it began collecting very high fees for water. And so there were “water revolts,” so-called, in Cochabamba, the community mobilized and eventually the government decided that it had to take back the utility. And at that time, Bechtel brought in arbitral lawsuit against Bolivia, but not as a U.S. corporation. It was under a Dutch-Bolivia BIT, bilateral investment treaty. So it claimed that it was a company from the Netherlands. And on that basis, it could sue Bolivia. The tribunal sided with Bechtel and allowed the case to proceed.

How common is it that the investment arbitration is used in this way, to question the courts of another country?

This case is not your run of the mill case in terms of the issues and the remedies that the tribunal has crafted. In that sense, it is surprising and it’s rather exceptional. It shows how far reaching the system can go. The more typical cases are the situations and claims where a government adopts a measure—it may be a regulation, it may be a law—that a company’s dissatisfied with. Because it increases costs, because it may impose changes in its modes of work or production. And in those situations, the company may resort to arbitral jurisdiction in order to receive a monetary remedy. That’s the more typical case. But what’s typical and what’s atypical, of course, then becomes a matter of perspective. And the fact that in this Chevron-Ecuador case, an award was presented in this way, may open the door for further expansion of the system. In the early 1990s, there were tens of cases presented every year. Today we’re seeing more than hundreds of cases presented every year. So this is a system that is expanding. So how common is it in that sense? Quite common. The question is, who is served by that? Is it contributing to development? Is it contributing to the protection of the environment and the public interests involved? Or is it a system that is advancing corporate profits at the expense of the government and its people? That’s the big question in the field. And many, many governments are asking themselves that question. After all, governments have signed up to these international treaties. And there are efforts underway at the United Nations level and elsewhere where governments are discussing whether this system is actually in their interest, in the interests of the public interests that they are constitutionally mandated to advance and serve. And so there are examples of some countries saying these treaties, we’re not going to negotiate them anymore. This arbitral system, we’re not going to consent to be bound by it.