The BBC, Guyana, and Untangling North-South Climate Complexities

An excerpt from a BBC interview with Guyana's president Dr. Irfaan Ali went viral on social media at the end of this week. In it, Ali chides the BBC journalist (and, by extension, the Global North) for being hypocritical on climate and points to Guyana's role as a carbon sink in the world. It's a glimpse into the complexities of the North vs. South dichotomy on climate and a perfect example of why we actually need to grapple with them.

Based on the various reactions to this video, it's clear that it's still far too easy for folks to boil this down to a debate of development versus sustainability, or to the decades-old idea that "it's only fair" for less developed countries to get a few decades to pollute for profit as well; after all the industrialized North did it. But the reality is: that's not what's happening in places like Guyana, Suriname, Uganda, and Mozambique, where the global fossil fuel industry is racing to exploit as much oil and gas as they can while it remains profitable to do so. These countries are not "getting rich" off oil any more than Nigeria got rich off oil (or Chad, or Venezuela, or any other less developed country hit by the oil curse since the 1980s). The only one getting rich off oil and gas, always and forever, are the transnational companies and state-owned oil companies that control the value chain, not the countries where the resources happen to be located.

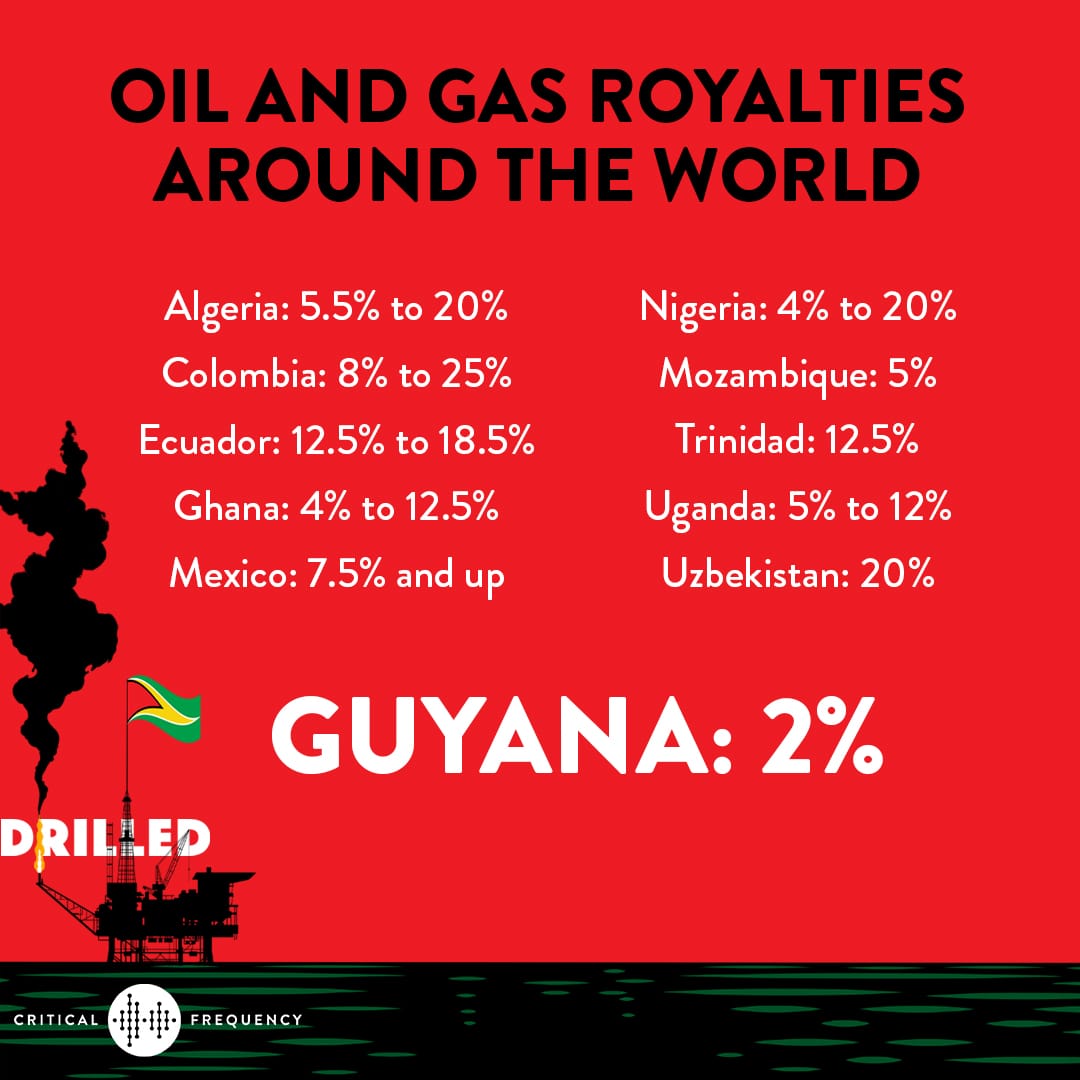

One need only look at the way contracts and royalties are structured to see that. Guyana has one of the smallest royalties in the world for the production volume Exxon is projecting there (more than its Texas Permian Basin projects by 2025, representing more than 25% of its global production), and a contract that has Exxon front-loading its take while Guyana won't see an equal share until long after experts predict the price of oil to have plummeted.

Even the IMF has called Guyana's contract with ExxonMobil “too generous to the investor” and noted that it contains “a series of loopholes,” that benefit Exxon, and that the royalty rate for Guyana is “well below what is observed internationally.”

In his defense of Guyana's oil industry, and its climate track record, what Ali is really racing to defend is elite capture—the benefits that Guyana's oil boom is bringing to himself and a handful of other elites in exchange for their willingness to do the bidding of ExxonMobil—and the perpetuation of oil colonialism. As political economist Keston Perry put it brilliantly on Twitter (no, I will never call it anything else), "Guyana is not responsible for climate change. We should all call out the hypocrisy and disrespect of the Global North. However, while forceful, President Ali can not be let off the hook for allowing his government to be used as a neocolonial puppet for Exxon, the U.S., and transnational corporations."

It's not the first time such interests have sought to extract value from Guyana. As Raphael Padula, Matheus de Freitas Cecílio, Igor Candido de Oliveira, and Caio Jorge Prado write in their excellent analysis of Guyana's oil boom for Phenomenal World, American interests in Guyana date back to the nineteenth century. The country has seen gold, bauxite, diamond and lumber booms over the years, none of which has left it better off economically. It's important to understand Guyana's colonial history and its decades-long experience with what political economists call "the resource curse" to understand what exactly Ali is defending today.

As it did in so many South American countries, the CIA involved itself in Guyanese politics during the Cold War and continued that involvement for decades. The country's first political party, the Progressive People's Party (PPP), was formed in 1950 with the goal of gaining Guyana independence from Britain. It was led by Cheddi Jagan, of Indian-Guyanese origin, and Forbes Burnham, who was Afro-Guyanese. In 1953, Guyana was granted home rule and Cheddi Jagan was elected chief minister, but the UK government was uncomfortable with what it called Jagan's "Marxist leanings," so within months it had suspended the constitution and the government and replaced Jagan with an interim government of its choosing. The Brits also warned their friends in the U.S. that Guyana was a "new Cuba" growing in South America. Under JFK's direction, CIA operatives began to stoke racial resentments in the country between its Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese communities, contributing to a split of the party along racial lines in 1957.

Jagan remained in charge of the PPP, which became a primarily Indo-Guyanese party (it's the party Ali is a member of), while Burnham started a new party, the People's National Congress (PNC), which became the primarily Afro-Guyanese party. Burnham was less of a radical leftist, and thus became the Global North's preferred political leader for Guyana.

Nonetheless, in 1961 when the Crown finally granted Guyana autonomy, Jagan became prime minister. The CIA stepped up its game, and the U.S. government funded various opposition groups to Jagan, inciting riots and violence and significantly weakening Jagan's power. It's an often overlooked chapter in America's Cold War activities in Latin America, but according to U.S. State Department archival documents, the government spent $2.08 million on "covert action programs" in Guyana from 1962 to 1968. And it worked. In 1964, thanks in part to the protests and in part to some creative electioneering orchestrated by the Americans, Burnham replaced Jagan and began rigging elections, mostly by padding overseas votes to stay in power, again with help from his friends in the U.S. and British governments. The Americans and the Brits had worried that Burnham was likely to become a dictator, but they were more worried about Guyana—a country absolutely brimming with natural resources—being led by a communist.

In the 1970s, Burnham and his backers faced a new challenge in the form of Walter Rodney, author of the classic text on imperialism, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. After lecturing abroad on neocolonialism and imperialism, Rodney returned home to Guyana determined to do something about these forces in his own country. He created and led a new, revolutionary political action group, the Working People's Alliance in 1974, devoted to ending racial polarization and removing Burnham from power. The WPA organized workers strikes and protests, and were met with violent opposition by Burnham's police force. After dodging multiple attempts on his life throughout the 1970s, Rodney was killed by an explosive in 1980, which his supporters said was a Burnham hit, but Burnham claimed was just a mishap with a bomb Rodney himself planned to detonate in the capital. In the same year, Burnham's government rewrote the country's constitution and Burnham was elected Guyana's first president.

The results of that history are, of course, layered and multi-faceted, but one outcome is that politics remain deeply racialized in Guyana (although both have been quite open to the fossil fuel industry—when the PNC was in power, the PPP vowed to renegotiate the contract with ExxonMobil, now that the PPP is in power, the PNC is making similar statements). Another is that it has created the conditions under which extractive colonialism has continued to feast on the country's resources. Oil is just the latest chapter in a very old story in Guyana.

Don't forget, we spent two years making a whole podcast season on Guyana, working closely with local reporter Kiana Wilburg in Georgetown. You can check that out here (or wherever you get your podcasts). Or start listening right now:

Something Guyanese attorney Melinda Janki said to me and our producer Sarah Ventre over lunch in Georgetown a couple years ago has always stuck with me on this question of whether it isn't terribly unfair to "deny" Global South countries like Guyana the right to develop fossil fuels. She was talking about a report that had suggested that the Global North curb emissions and fossil fuel development first to allow Global South countries more of the global carbon budget, an idea that seemed eminently fair on the face of it (if quite patronizing), but it enraged Janki.

"Why would you say that?" she said. "When in every single former colony, people are saying, 'Stop the oil. We don't want it.' In places like Uganda and Mozambique, they're putting their lives on the line to stop oil and you sit in your comfortable university room and say, 'Oh, well I've decided that in the interest of justice, these people shouldn't have to get rid of fossil fuels until 2050. And in order to make this really fair, the first world should now immediately convert to renewable energy. In other words, all the white people, go straight for renewable energy, realign their economies and move on to prosperous carbon-free futures. Dump the stuff on the third world. But I'm doing this under the guise of a just transition."

I'll admit, I hadn't thought about it this way before she said it, but it immediately made so much sense. I felt the same way when Daniel Ribiero, a researcher and climate advocate with Justiça Ambiental in Mozambique rolled his eyes at the idea that Global South countries will ever realize the sorts of financial gains from fossil fuels that the Global North did.

"This notion that Europe and the U.S. developed with gas, coal and oil and now it's Africa's turn, that's just a huge lie," he said. "The North developed with colonialism! Colonialism, stealing our resources, enslaving and exploiting our labor. But also even if you eliminate that phase, we are not allowed to participate in the value chain, and we never have been. These countries developed because of the research, the patents, the technology, the manufacturing, the transport, the markets, the companies, they controlled the value chain. So you could put anything at the bottom of the value chain, be it alternative energies, be it oil, gas, even if it was human feces as our main fuel to develop, the value chain is what makes that work. Africa does not have access to any of that. We can only be extracted from, and from then onwards we have no part in it. That's why we have no examples of any African country developing with fossil fuels. It's not possible. This is a false narrative that is being sold just to get support from the masses because right now, short, easy, superficial narratives have a lot of traction, and to be able to explain the full picture, it takes more time, more complexity and the attention deficit generation is not very well adapted to that."

It's important to understand these complexities because they are currently being flattened not just by corrupt government officials in Global South countries or fossil fuel executives in Texas, but also by a whole ecosystem of pundits like Jordan Peterson, Michael Shellenberger, Alex Epstein and even Joe Rogan, who use the idea that fossil fuel development will solve poverty in Africa as justification for continuing fossil fuel's dominance in the world. In fact, fossil fuel development hasn't even solved energy poverty in the African countries that have embraced it; Nigeria has the continent's largest and oldest fossil fuel industry and yet still has the world's lowest energy access rates. Oil majors aren't in these countries to help them, they're there to exploit resources. If destroying democracy while they do it adds a few pennies to the bottom line, so be it.

In his excellent book Private Empire, about the way Exxon operates around the world, Steve Coll describes an industry meeting in D.C., where an exec from another company asked former CEO Lee Raymond if Exxon would consider building more refineries in the U.S. to help protect Americans against potential gas shortages. "Why would I want to do that?" Raymond answered. "Because the United States needs it...for security," the exec countered. "I'm not a U.S. company and I don't make decisions based on what's good for the U.S.," Raymond said. Similarly, he found it irritating when people would question why Exxon was supporting unethical dictators or repressive regimes in some of the countries in which it operated. It was Exxon's policy not to get involved.

"The issues of concern to ExxonMobil were primarily the production of oil and the sanctity of contracts," Coll writes of the company's approach in Equatorial Guinea, where human rights abuses were (and are) flagrant under dictator Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. "'We are an oil company; we are not the Red Cross,' as Andre Madec, an ExxonMobil executive who oversaw global community relations, once put it. 'We don't want to be seen as the defacto administration.'"

As in Equatorial Guinea, and Chad, and the many other countries in the world in which Exxon operates, its interest in Guyana lies in getting as much oil and gas out from under the sea floor as it can, and making as much money as it can from those resources, as quickly as it can. "I think sometimes people don't realize that the purpose of the oil company is to make money and they have no other purpose," Janki said. "They're not there to promote human rights. They're not there to protect the environment. They're there to put the share price up and to give big, fat dividends to their shareholders."

It's one of the two key lessons she said she learned while working as a lawyer for BP in London. "The other thing I think I learned was that they're very efficient, very, very efficient at what they do," she said. "They're very good at what they do, and they're very good at telling people a story about how beneficial this is for the world. The oil industry always tells you how good it is for you to have them, how your life is much better because they're there. And that has a way of removing every other narrative."

The key "other narrative" in this case is climate change. Guyana, as Ali pointed out, has contributed nothing at all to climate change—in fact the country's protected forests are a massive carbon sink for the world—and yet it is extremely vulnerable to it. 90 percent of the country's population lives on a tiny coastal sliver that's projected to be under water by 2030, thanks to sea level rise.

ExxonMobil, on the other hand, has contributed quite a lot to climate change, both in terms of the emissions that drive it and in terms of its efforts to block any sort of action on it. Exxon has played no small role in undermining the international climate negotiations intended to help countries like Guyana pay for climate adaptation; now Ali and his VP Bharat Jagdeo regularly talk about how the oil money will help them pay for things like sea walls and moving people out of the ocean's way.

Climate reporters and climate advocates have both tended to miss the forest for the trees here. Rather than questioning President Ali on Guyana's climate record or his decisions on oil, we should be questioning him on his relationship with ExxonMobil, whose executives are regular guests in the president's box at the cricket stadium, where the Exxon-sponsored team plays, for example. We should be asking how Guyana ended up in the position of needing Exxon's money to pay for climate adaptation, what role Exxon played in creating those circumstances, and what the Global North can do to hold these companies accountable...not what we can do to help them further plunder the Global South. To state what I hope is an obvious point: helping ExxonMobil get rich off Guyana's oil is not justice, climate or otherwise.

This Week in Information Pollution

We're working on a story that will be out soon about a new LNG lobbying group that's focused on getting European leaders to extend contracts and support import infrastructure, even as the continent's gas consumption continues to drop. Their main message is that LNG is a climate solution because it's replacing coal and enabling a larger buildout of renewables. Those claims are highly debatable, and debate them we shall, but the way the group operates is also a great example of what we call the "enabler ecosystem" around the fossil fuel industry. Because not only does it include various LNG producers as members, it also includes think tank leaders and academics—folks from The Atlantic Council, the Progressive Policy Institute, and the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability—on its "Advisory Council." The presentation it has been giving to both European and U.S. lawmakers to sell this idea of LNG is the world's best climate solution? It was researched by management consulting giant McKinsey. The meetings it's having with EU Commissioners on energy? They were set up and moderated by global PR firm Fleishman Hillard.

Sometimes reporting on the PR industry, think tanks, university research and management consultancies can feel a bit abstract—it seems vaguely "bad" that fossil fuel giants are spending so much money on all of these things but we're rarely told exactly why it's bad. Here we see the creation of skewed data that supports a greenwashing claim, the connecting of a front group to powerful politicians that can ease the path for their industry, and credible-looking "research" that backs up a greenwashing claim. All in the service of a pretty small potatoes front group in the grand scheme of things. If all that is going into one group's efforts, it's easy to see how much this ecosystem is making off of the industry and continuing to prop it up.

This Week's Climate Must-Reads

- Boston Review: The Judicial War on Government - An excellent rundown from Lisa Heinzerling of what's really going on with all this sudden attention on "Chevron deference."

- SF Federal Reserve Report: Extreme Heat's Disparate Impacts on a Local Economy - This is a really interesting look at the economic impacts of extreme heat that quantifies, for example, lost income for outdoor workers: 41 days of work lost due to extreme heat by 2065 (although Boston University climate risk expert Madison Condon pointed out that this sort of analysis should also include the economic loss from the stuff those workers could have been doing in that month and a half.)

- Splinter: The Magical Thinking Behind Global Climate Ambitions - The great Dave Levitan on the limits of techno-optimistic climate solutions and the fantasies baked into so many climate roadmaps.

- Inside Climate News: International Court Issues First-Ever Decision Enforcing the Right to a Healthy Environment - Katie Surma reports on a landmark ruling from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights that will have far reaching implications for communities affected by extreme pollution.

- The Guardian: Baltimore Bridge reporting from Dharna Noor - One of The Guardian's climate and fossil fuels reporters, Dharna Noor, lives in Baltimore and has been covering the bridge collapse from multiple angles; it's a great way to keep up on this evolving story!