The Trouble With "Market-Based" Climate Solutions

Over the past several months I've been working on three stories that, on the surface, don't have much to do with each other. They were focused on: fossil fuel funding of university research, Exxon pulling funding from algae biofuels research, and the country of Guyana emerging as a new oil state.

The line that keeps popping to mind when I think about each of them, though, is: this is what happens when you leave a problem like climate change to "the market" to solve. In the case of university funding, several researchers and university administrators said similar things to me, along the lines of "well if we're not taking oil company money to study drilling, I don't see the problem," or "if they're funding solutions, that should be welcomed." But those takes ignore the way that money can warp what's considered a viable solution. Fossil fuel companies primarily fund research into the technological "solutions" to climate change that don't require ditching combustion engines or fossil fuels: biofuels and carbon capture. They also like to fund public policy schools, economics programs and legal centers that push for a particular understanding of "the market" and fossil fuels' role in it.

Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon) was an early mover in this realm. Back in the 1940s and 1950s, former Exxon VP Frank Abrams was regularly making speeches at various industry gatherings about how valuable university donations could be to not only the fossil fuel industry, but corporate America in general.

"Education, more and better education, is needed if we are to maintain that most cherished of man’s works—a free society," Abrams said in a 1953 speech. "There is a tendency on the part of some people to call on the government to take over more and more functions and responsibilities borne previously by citizens, acting as individuals or in voluntary associations. In each case, the claim is that private or voluntary group initiative has failed; that the public can better be served by a new government bureau. Each time government takes over a new function the free society shrinks by that much. A step has been taken toward statism, a system holding great dangers for the general well-being of the country, and incidentally, for stockholders’ investments in corporations. This is a problem with great dimension, in my view, but I think finally we can rely on a prudent and mature people— that is, an educated people—to deal properly with it."

The justification a lot of researchers give for welcoming large sums of fossil fuel research funding is that these companies also help to ensure that academics aren't just following some crazy idea, that they're sticking to what will work in the real world, giving "the market" what it wants. But what if we need crazy ideas that ignore the market to actually address the climate crisis?

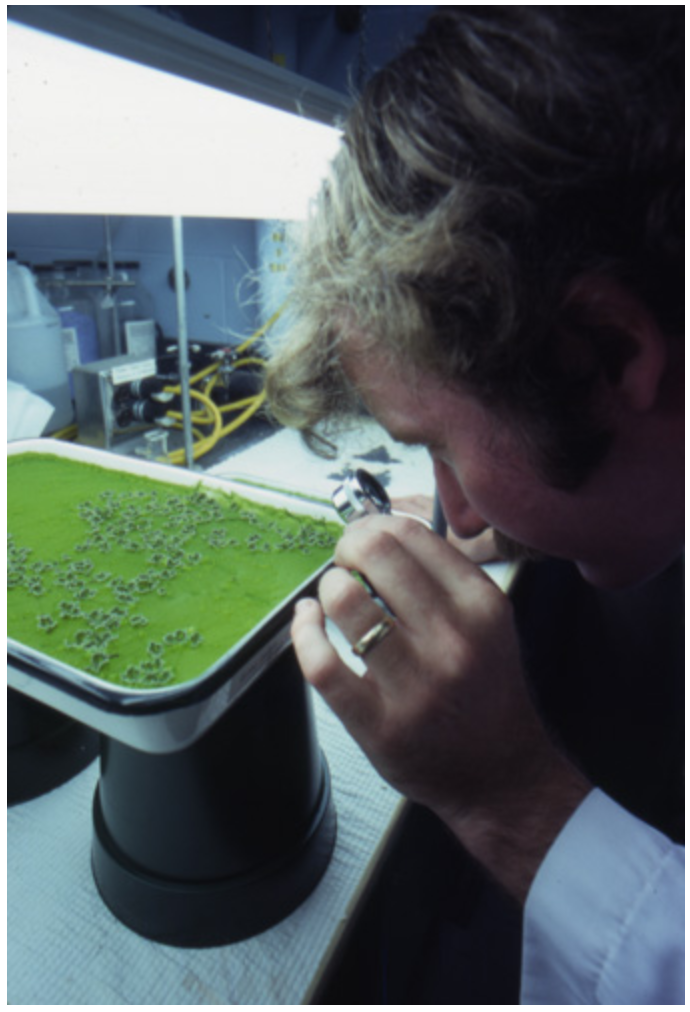

The story of what has happened to algae research for 50 years is a really good example of where neoliberal approaches to research funding can go wrong. First, in the 1970s, when OPEC imposed an oil embargo against the U.S. and there were growing concerns about peak oil, funding went into all sorts of alternative energy sources—solar, wind, lithium batteries, nuclear and, yes, algae. Then the embargo ended, the oil shortage was replaced by an oil glut, the bottom fell out of the oil market and most of that research funding went away.

In the lead up to COP 15 in Copenhagen, when it looked like the world might actually coalesce around binding climate commitments (spoiler alert: they didn't), every oil major had a big biofuels play. BP invested $500 million in university (they only wound up investing around $300 million) biofuels research, Exxon pledged $600 million to fund algae biofeuls (they ended up investing around $350 million), Chevron, Shell, they all had an algae play. Then the fracking boom went bust and all but Exxon pulled out. Now as electrification of transportation is increasingly taking hold, Exxon too, is out. The market has spoken! But...what if algae biofuels would have been a better solution, had there been real money put behind them? Or what if all the money the industry put into algae fuels actually delayed electrification? And why can't we talk about the outsized role corporations are playing in shaping what sorts of solutions--whether political or technological--we're allowed to even consider?

So...where does Guyana fit into all this? Well, there again, what do we hear constantly about the need for funding that will enable the Global South, which will bear the brunt of the climate crisis despite contributing to it the least, to adapt and transition? We have to leave it to the market! "No government in the world has enough to plug the hole of those trillions," U.S. climate czar John Kerry said at last year's COP. Kerry said that money would need to come from the private sector, especially banks and other large financial institutions. In the absence of money from either governments or banks, Global South countries with oil reserves—like Guyana—are turning to oil majors to plus the hole. The market has left countries on the front line of the climate crisis with no one to turn to for help but the corporations that caused the problem in the first place.

Our new podcast season is a crossover between Drilled and Damages and takes a close look at the idea that oil can save the Global South from either poverty or the climate crisis, through the story of what's happening in Guyana. First episode drops Tuesday next week, but paid subscribers can access it early here. Here's the trailer:

This week's climate must-reads

- FirstEnergy and Larry Householder guilty in RICO case (Bloomberg) A jury found former Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder guilty in a RICO criminal case involving $60 million in dark money bribes paid by FirstEnergy to block solar and extend the lives of aging coal and nucear plants. It's a real accountability win with potentially wide-ranging implications.

- Why Is the Fossil Fuel Industry Praising the Inflation Reduction Act? (The New Republic) - At the indusry's annual conference, CERA Week, fossil fuel execs are applauding the IRA, because they're successfully leveraging it to their benefit.

- A Plan to Ship Oil Along the Colorado River Sees Revived Opposition Amid National Railway Safety Debate (Inside Climate News) The proposed railway would send up to 350,000 barrels of oil a day from Utah to the Gulf Coast via the national rail network, running along the Colorado River for more than 100 miles.

- BBC will not broadcast Attenborough episode over fear of ‘rightwing backlash’ Narrated by David Attenborough, the new series has five episodes scheduled to go out in primetime slots on BBC One. A sixth episode, a stark look at losses of nature in the UK and what has caused them, is apparently only going to be released on BBC iPlayer due to concerns that rightwing politicians will have a problem with certain themes discussed in it, particularly the concept of "rewilding."

- Study: Future warming from global food consumption (Nature Climate Change) This study uses a simple climate model to show the disproportionate impact of methane emissions from agriculture on temperature increases, and throws light on the importance of reducing methane emissions from the food system, in particular