Podcast: Why Is One of Big Oil's Top Greenwashing PR Firms Handling Media for COP27?

The conference of the parties or COP, the annual global UN climate negotiations, have kicked off in Egypt, and I'll be digging into a few aspects of it over the next couple of weeks. This week, I wanna talk about greenwashing and how it's made its way into these proceedings really since they began back in the early 1990s.

You might remember a guy named E. Bruce Harrison who's come up quite a bit in the podcast over the past couple of years. Back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Harrison saw these international climate meetings coming a mile away, and he helped his oil and gas clients strategize to ensure that climate commitments would always be voluntary, not mandatory. He created an industry group called the Global Climate Coalition, whose job was to make sure that international climate talks never resulted in anything binding.

"I mean, the GCC supported the passage of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change," says Robert Brulle, an environmental sociologist at Brown University, and author of a recent peer-reviewed study on the GCC. "They supported that in 1992. Because it was toothless, you know? Oh yes, we need to further study these things, and of course we need to do this and everything will be voluntary. And then of course when Clinton says 'mandatory,' they go, 'Oh, no, no, no, you can't have that. ' And you know, they lobby like hell and get a voluntary action plan, voluntary initiatives to reduce carbon emissions, yada, yada, yada."

"And so by 92, they already got a template, they've already got an organization," Brulle adds. "They've got their rhetoric down, they've got their organization down. There is a playbook."

When the world did get close to enacting a binding treaty on climate, the Kyoto Protocol back in 1997, it was the GCC that killed it.

" These are the guys like, Whoa, what do we do? Well, let's do this. And they, you know, they played around and made a couple mistakes here and there, but they got the playbook and they got it down and they destroyed the Kyoto Protocol," Brulle says. "And well, now we know how to play this game. And we've got a playbook, and we have a cadre of people that know how to make this happen."

"They say, 'What works? Well, when you can attack the science, do. Play up the economics. Play up the economics, play up the threat to the American way of life. Talk about international inequality, talk about energy security.

A lot of the talking points they crafted back then are the same ones that are being trotted out today. The Global South has been used in the past as an excuse for the Global North not to act on climate. The story back in the 1990s was well, if they don't have to comply with these emissions reductions, why should we? Now, it's being used as an excuse for the Global South not to act on climate. The new story is that it's unfair to stop the Global South from developing and profiting from fossil fuel resources. Except, who's really profiting? If you look at the contracts these companies have signed, it's oil companies from the Global North, specifically Europe, the UK, or North America. The industry changes its narrative depending on what suits it.

"They're cultural opportunists," Brulle says. "I mean, all this compassion for global poverty, and the only way to get 'em out of it is fossil fuels. Which, one, no, that's not true. And two, you know, is a colonialist attitude of telling people how to figure out their own lives. Thank you very much, they can reason for themselves. Suddenly the fossil fuel industry has this faux concern over the Global South because it fits their argument. Anything that supports their position, they'll grab onto. It's just opportunism as far as I'm concerned. Because if they were really concerned, there's all kind of things you can do. I don't see you joining any of those groups."

So from the very first cop oil companies, and importantly, their PR firms have played a major role in determining the outcome of global climate negotiations, which is why it was pretty shocking to learn that the government of Egypt, this year's host country, selected the firm Hill + Knowlton to handle media for COP. Hill + Knowlton have been handling briefings and press conferences for months leading up to the conference. That name might sound familiar to listeners of our podcast, because like Harrison, their founder, John Hill, was the focus of an episode in our Mad Men season a couple years back.

Hill and Knowlton not only masterminded Big Tobacco's deception strategy back in the 1960s, they also worked for the fossil fuel industry during those years, and were a conduit of information between the two industries. Talking about the similarities between Big Tobacco's and Big Oil's strategies without talking about John Hill leaves out an important piece of the history.

And Hill + Knowlton's conflicts of interest aren't in the distant past either. Today, the firm handles media for the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, a coalition of the world's 12 largest oil and gas companies, and a central hub for all of their greenwash messages, from meaningless net-zero pledges on carbon to the hilariously named Aiming for Zero Methane Emissions Initiative, which will be a major force in negotiations on methane emissions at COP this year. It's hard to imagine that the Hill and Knowlton team handling PR for COP isn't feeding back immediately to the team that handles the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative. With that in mind, I thought it might be worth taking a look at the history of Hill and Knowlton, its founder John Hill and its role in crafting climate denial.

"When you look behind the veil, you find that it's the same companies. It's the same firms. Often it's the same people providing these services, and nowhere is that clearer than for example, With the role of Hill and Knowlton," says Carroll Muffett, CEO and executive director of the Center for International Environmental Law.

Muffett has quite a bit of information and documentation that has never been published on the various public relations firms that have worked with the fossil fuel industry, and specifically with both the fossil fuel industry and tobacco. "Hill and Knowlton, which is widely recognized as a lead advocate for the tobacco industry in the Tobacco Wars was simultaneously and from a very early stage, also actively representing an array of oil and gas companies on the issues of concern to them. And often the same account leads on the tobacco campaigns were also account leads for oil companies," he says.

John Hill was born on a farm in Indiana in 1890. His grandfather had been wealthy, but his father lost all the family's money in a series of business deals gone wrong, and Hill would spend the rest of his life chasing the company and approval of rich men. Like a lot of PR guys, he started his career as a journalist, but unlike the others, he seems to have been fairly good at journalism.

While most PR folks spent a year or two struggling to make journalism happen before switching to comms, Hill was a financial and business reporter for 17 years before he got into the PR game. He even started a couple of newspapers himself, although he struggled to keep them afloat.

His first foray into PR came in 1920 in Ohio when he took a gig creating a newsletter that Cleveland's Union Trust company wanted to send out to local executives. By this time, he was the financial editor of a steel industry trade magazine (because Ohio). These jobs put him in regular contact with executives who complained to him constantly that most reporters were inept at numbers.

They also introduced him to a lot of influencers and executives in the area, and eventually Hill saw a niche that he could fill, helping companies explain themselves to reporters who didn't get it quite as well as he did. Hill opened up his own firm in 1927 with Union Trust and Otis Steel as his first clients. Because Hill was well liked by local executives, word spread fast and within a couple months he'd built an impressive roster. It included United Alloy Steel, Republic Steel, and Standard Oil of Ohio. The Standard Oil account was an important win for Hill. He was a huge fan of the first modern publicist, Ivy Lee, who pioneered various techniques as Standard Oil's publicist for several years.

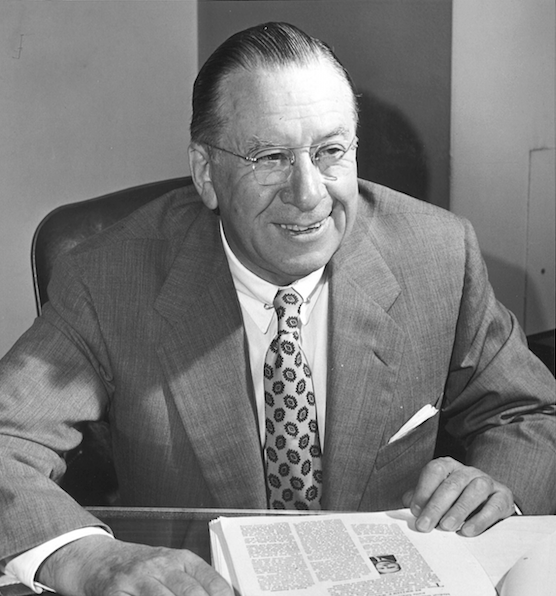

Hill hated how flashy many of the other PR guys of his day were. He preferred Lee's distinguished Southern gentleman shtick and he emulated it. Like Lee, he preferred to stay behind the scenes. Although Hill took it to an extreme, almost never appearing in the press. When he did show up in public, it was always in a conservative suit, clean shaven, hair slicked back, wire-rimmed glasses.

But just when his business was starting to take off, the stock market crashed. Hill's steel and oil clients weathered the financial storm okay, though. And Republic Steel helped to score the firm a whale, the American Iron and Steel Institute, the trade group for the whole industry.

They requested that Hill and Knowlton open up a New York branch near their headquarters in the Empire State Building. That same month, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office. Hill hated the New Deal and so did most of his clients. Standard Oil had him write up an advertorial assuring people American business would be okay, and his steel clients had the firm cranking out pamphlets emphasizing the great relationship between steel workers and their managers.

The reality, of course, was that steel workers and their bosses had been fighting for a long time, and America's big steel companies had done everything they could to repress unionization as the largest industry in the country and the largest employer. The steel industry kind of viewed itself as the last defense against unionization. A protector of American business, defender of bosses, everywhere. They were helped in their efforts by near constant concern about creeping communism in the U.S. Starting with the 1919 red scare and continuing for decades, anti-union pamphlets Hill and Knowlton made for Republic Steel highlighted how union shops actually infringed on workers' rights.

They argued that closed union shops denied the rights of the individual worker to make his own choices as to whether he wished to belong to a union. It's the exact same line you see in anti-union ads today. Another Hill & Knowlton client, the National Association of Manufacturers, one of the earliest industry trade groups, went beyond pamphlets to sponsor a weekly business-friendly, anti-New-Deal radio drama called the American Family Robinson.

'It's time to join the American Family Robinson again in Birch Falls," one episode went. "But one thing this army situation ought to get credit for is bringing everybody face to face with the cold facts. That's right. And there ought to remind the country of something more specific that it's only business and industry that can provide soldiers and sailors with the proper equipment."

But after more than a decade of suppression, the labor movement was gaining steam. A few years after opening his firm's New York office, John Hill faced his first big challenge in PR and just like with his hero, Ivy Lee, it came in the form of a violent labor strike. Steel workers were starting to band together by 1936, forming the Steelworkers Organizing Committee within one of the country's biggest unions, the CIO.

This officially freaked steel bosses out. The American Iron and Steel Institute put Hill and Knowlton on the case, and they wrote up full page ads with a manifesto for the industry. The ad suggested that outside agitators had coerced employees into joining the union. On the last day of June and the first day of July, 1936, the trade group sponsored full page ads in 382 newspapers in 34 states.

But the unions persisted. In 1937, US Steel agreed to recognize the unions and negotiate a contract that made it more difficult for the other companies to resist. But there was one holdout: Little Steel, an umbrella group that included all the smaller independent steel companies, led by a man named Tom Girdler, president of Republic Steel Hill and Knowlton's client.

They refused to have any sort of contract with a union. And then in May, 1937, Girdler was elected president of the trade group. Apparently by this point he had been stockpiling weapons for months, planning on some kind of armed battle with the union. Later that month, a strike began at the Republic Steel Plant in Chicago.

Armed strikers and armed police in front of a South Chicago steel plant. The union quickly branded the event the Memorial Day Massacre. They held a mass funeral in Chicago, attended by hundreds of working class residents.

Then another riot broke out at another Republic plant. This time in Youngstown, Ohio. The FDR administration was having none of this. By October, the National Labor Relations Board had ordered the companies to reinstate more than 7,000 workers with back pay. Then the Senate launched investigations into the steel bosses' methods.

Because of Hill's involvement in pushing anti-union messages and ads and newspapers. He was caught up in this investigation too. Senator Bob Lat discovered that not only had John Hill placed ads, he had successfully bribed a journalist. George Sokolski, a columnist for the New York Herald Tribune frequently wrote about free enterprise and anti unionism in magazines like The Atlantic Monthly from 1936 to 1938.

Sokolski received $29,000 from Hill + Knowlton to write anti-union articles for the steel industry trade group, and it worked. He wrote stories in prestigious newspapers and magazines about how the riots were all the union's. Never disclosing his connection to Hill + Knowlton or the steel industry. Sokolski also regularly ranted on the radio for the National Association of Manufacturers and various other pro-business groups.

"The federal government’s Social Security Act passed by Congress, signed by the president, is now the law of the land. When we think of that, we have something very specific before getting close to $5 billion dollars annually within the next 15 years will be met by taxes, which refers to increased prices, reduced profits and possibly even reduced employment of labor," he complained about that terrible socialist policy, social security,

The dude was like a Progressive era, Rush Limbaugh. Ultimately, World War II rendered the whole labor argument moot. The factories were required to unionize, but the war also kicked off another Red Scare, further solidifying Hill's conservative pro-business, anti-government ideology, and it's that ideology that fueled his work for his next big and lethal client.

Post WWII

World War II had just put an end to years' worth of labor strikes in steel mills. John Hill was hired to help the industry through it all, but his work on that front was basically a failure. Not only had his clients lost the war with labor, but their tactics had been outed in the press. They looked just like the evil bosses they were pretending really hard not to be. A lot of people would've lost those accounts for bungling the labor strikes so thoroughly. Hill had read the room entirely wrong. And not only that, he'd gotten busted bribing a journalist! But by this point, the steel and oil barrons who made up Hill's clientele considered him a friend, an equal, a trusted confidant.

And he spent almost as much time managing how his clients saw him as how the public saw them. By this point, Hill had also learned a very important lesson: His job was not to sell the public on any particular product, company, or industry. It was to sell Americans on the importance of American business in general, and particularly big business.

He was pushing ideology, creating social license for American industry, and that meant working in Washington too. Shortly after the War, Hill and Knowlton became the first PR firm to have an entire branch dedicated to public policy. The Washington office didn't have its own accounts. It existed solely to handle government relations for the firm's New York and Cleveland clients.

That meant they had their hands in everything from energy policy to agriculture and all points between for clients like Texaco, Marathon Oil, Coca-Cola, Monsanto, and a big new client, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee.

It's a really good example of the type of strategy Hill would typically recommend for industries, and it shows how adept he and his firm were at manipulating the press. It also shows how big of a link Hill was between tobacco and oil. Not only did he have oil clients early on who informed some of his work on tobacco and vice versa, but he often brought them together in the same trade groups. RJ Reynolds, for example, a key member of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee also had their research arm join the American Petroleum Institute (API), a client of John Hill's by this point. And then there was the more direct intersection, which Carroll Muffett pointed out to me.

"Gas stations were the most important retail outlets for cigarettes for decades, and for the oil companies cigarettes were their most important retail product. Other than gasoline itself," he says.

That helps explain why there were so many overlapping ad campaigns between the companies. Muffett says there are two things that make this remarkable. One was the joint marketing strategies and documents and analysis that the oil companies would put together with the tobacco companies. The tobacco industry archives are filled with these strategies and reports, and many of the joint ventures were between two Hill and Knowlton clients. "So by the time you get to the 1980s and 1990s, we were finding joint meetings of advertising managers from Exxon Mobil and RJR or for Chevron and ConocoPhilips," Muffett says. "And these meetings were not just quick debriefs either. They would often include detailed requirements about where the cigarettes would be posted, what aisles they would be visible to ensuring that they were set up next to the candy. One of these reports runs to 200 pages and includes incredibly detailed analysis that broke people down by demographics, by neighborhoods, by socioeconomic status, with the goal of targeting them very individually."

Their entanglements eventually went beyond advertising "And so it's perhaps unsurprising, though it's also very little known, that the oil and gas companies actually ended up as defendants in the tobacco suit," Muffett says.

I double checked the tobacco industry archives when Muffett told me that and there they were:Texaco, Chevron, Exxon, and more, all named defendants in the tobacco suits, "Even less understood, and the thing that I think we found most striking, was that when tobacco companies needed to assess the toxics in their cigarettes and in cigarette smoke, the people they turned to to do it were oil companies," he says.

Remember, by this point, the oil companies had had their own air pollution issues because of smog and lead in gasoline. So they had all the equipment necessary to do this sort of testing at the time. And it's also worth repeating that John Hill repped both the main oil industry group, the American Petroleum Institute, and the main tobacco industry group, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee.

"And when the oil companies reported back to the tobacco companies on the toxins they were funding in that smoke, you know, what did they do with the information? Did they go public and say there's a massive risk here? No," Muffett explains. "Instead they entered into a joint enterprise with the oil companies agreeing to make cigarette filters for big tobacco, a product that's now one of the most ubiquitous plastic pollutants in the world. And the leaders in developing them were Exxon and Shell, and they did it because they saw marketing opportunity and a market opportunity in capturing the smoke. And of course for tobacco, it wasn't just a handy defense against rising health concerns around smoking."

It was also a chance to sell more cigarettes.

"It's really worth recognizing that as part of the tobacco litigation both the filter manufacturers and the tobacco companies understood all along that those filters were a marketing tool," Muffett says. "They understood that they did virtually nothing to reduce the toxic nature of cigarette smoke. And those filters did more than just create a new product stream for the oil and gas companies and create an excuse for the tobacco industry to continue selling cigarettes. They also started showing up in the environment over and over."

Today, every time you see one of those inventories from beach cleanups or big ocean plastic cleanups, one of the top five items they collect is always cigarette butts because of the filters.

So while all of this back and forth is happening between the oil guys and the tobacco guys, Hill + Knowlton has their staff funding and sourcing research on all the other things connected to lung cancer, and they're looking for scientists to sign on to the advisory board of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee. This was all Hill's brainchild. The tobacco companies initially argued that they didn't want to do a whole separate research committee. They'd already done their own research and they thought that Hill should just be pushing that instead of trying to get them to fund more studies. They didn't need a whole independent research committee. But Hill insisted they needed third party independent research that would be perceived as more credible than the company's own research by the media and the public.

Eventually they gave in. In December, 1953, the CEOs of all the major American tobacco companies met with Hill at the Plaza Hotel to launch the Tobacco Industry Research Committee. Now, they just needed a reputable cancer researcher as their scientific director, and that was not easy to find. So in the first several months of the committee's existence, its research was conducted by Hill and Knowlton staffers.

There are all of these internal staff memos from this time where they're giving updates on clients and the oil-tobacco connection is stark because you've got updates on Texaco followed immediately by updates on this phony research committee with lots of the same staff on both. Eventually, they hired Dr. Clarence Cook Little. He went by CC. And Hill + Knowlton proclaimed him a world renowned cancer researcher, which was a bit of a stretch. He'd been president of the University of Michigan and had worked for a year as the managing director of the American Cancer Society, but he'd never actually done any cancer research. The "cancer lab" that Little ran raised mice for actual researchers to use. In the hands of Hill and Knowlton, though, Little became a widely respected researcher, so much so that in May, 1955 when famed journalist Edward R. Murrow wanted to tackle the smoking controversy in a two-part special, Little was introduced like this:

"The cigarette industry, aware of this fact and fully cognizant of its responsibility, has organized the tobacco industry research committee. Its scientific director is the eminent cancer investigator Dr. Clarence Cook Little, head of the Jackson Memorial Laboratory at Bar Harbor."

The research group arranged for Murrow to talk to two other independent scientists, both of whom were also on tobacco's payroll, unbeknownst to Merrow. And the resulting documentary actually had the effect of making the legit scientists who hadn't gone through Hill and Knowlton's extensive media training look like activists and the industry plants looked like the serious, logical adults in the room.

Although he officially retired in 1962, John Hill remained very involved in his firm, going to the office daily, right up to a month before he died at the age of 86 in 1977. Hill had stayed true to his commitment to stay out of the press himself, and none of his industrial machinations were well known at the time of his death. His New York Times obituary sounds like it could have been written about any kindly octogenarian at the time. "Always conscious of his health, Mr. Hill lunched daily on cottage cheese and fruit or prune whip," it read. "He worked out in a gym two nights a week. He rode his own horses around his place in Pauling, New York on weekends frequently with business executives who also love to ride, and spent two weeks each year bareback riding in Arizona."

Yep. Prune whip, bareback riding and manipulating Americans.